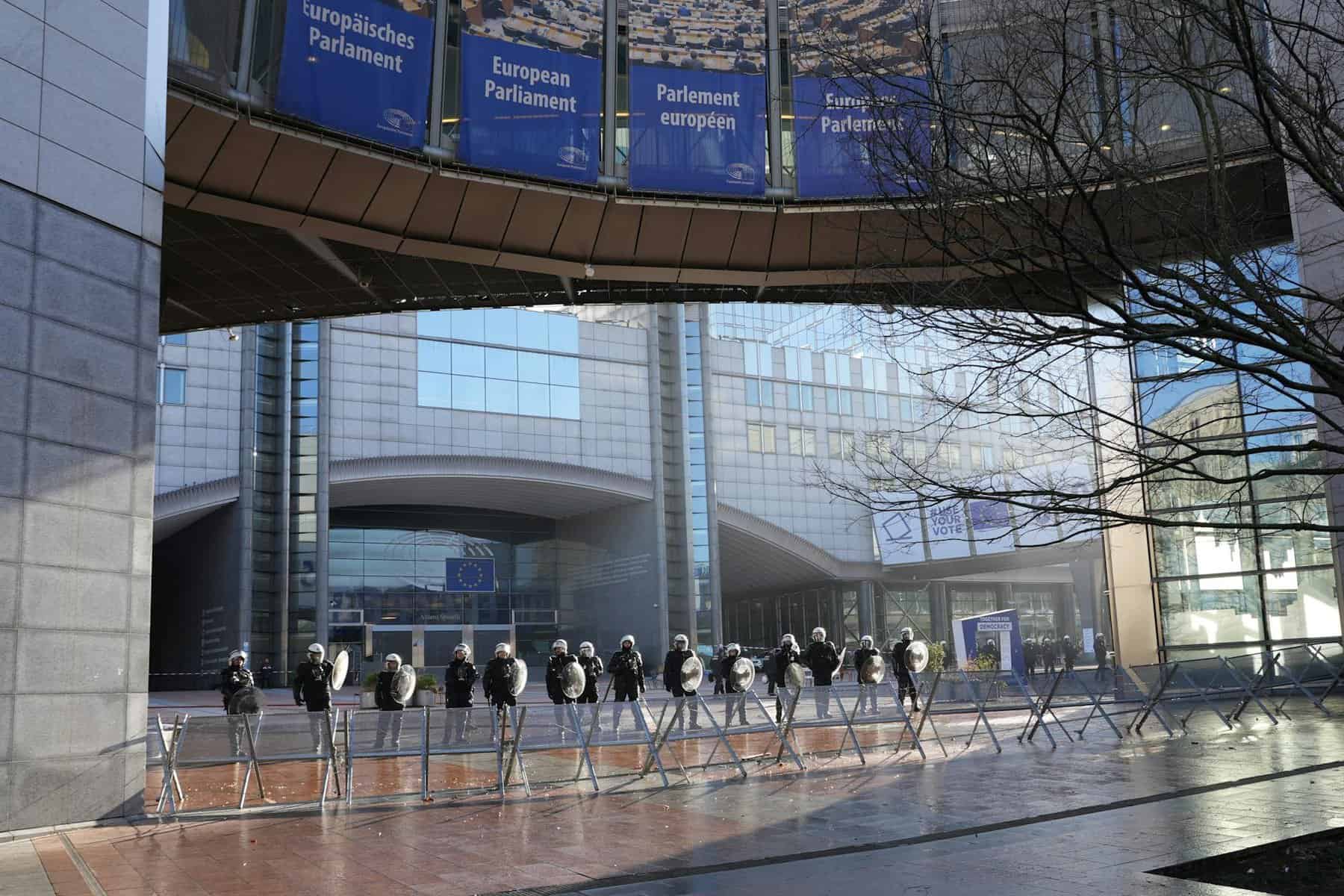

Still catching up with the backlog from my MA reading course, here are my notes on the second text we read this term. After the “green wave” of 2019 was followed by a blue/brownish one in 2024, it’s easy to believe that EU support as a political force has vanished into thin air. Carrieri and colleagues beg to differ. They argue that the EU dimension still matters, and not just in a negative way: to quote the abstract, “the more vocal a Europhile party, the more likely that citizens will vote for that party given their positional closeness to the EU.”

Carrieri, L., Conti, N., & Loveless, M. (2024). EU Issue Voting in European Member States: The Return of the Pro-EU Voter. West European Politics, online first(), 1–28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2024.2370121

What we liked

For whatever reason, my students love robustness checks. Give them some extra tables with alternative specifications, and they will be happy. The authors deliver on that front, and so that was the first positive I jotted down.

The other plus the students mentioned was that the research question and hypotheses are clearly spelled out. Students said that the argument is complex but presented in an accessible way. Kudos.

What we did not like so much

This is a very busy article that tries to do a lot of things—probably too many. We did not quite understand where EU entrepreneurship comes in. This intellectual complexity is also reflected in the statistical model, which, according to my students, is absolutely overloaded with complications, including several three-way interactions. I tend to agree.

Another fundamental question that emerged is whether the operationalisation of EU polarisation makes sense. If our reading is correct, the authors use the simple (signed) distance from the national median/mean. That implies that the variable actually captures pro-European positions (or their rejection), not absolute distances from the mean that are extreme (independent of their direction). If we are right, that would/should change the interpretation of the results.

Finally, the data relate to the 2019 (=green wave) election. Haven’t things changed quite a lot since then?

Take-home messages & further questions

2019 was a particularly interesting election, and even today, one should not underestimate pro-European parties and their voters. The real take-home message, however, is to always closely check the empirical results on which interesting claims are based.

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Likes

Reposts