Update

- Arzheimer, Kai. “Another Dog that did not Bark? Less Dealignment and More Partisanship in the 2013 Bundestag Election.” German Politics 26.1 (2017): 49-64. doi:10.1080/09644008.2016.1266481

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [HTML]Using new data for the 1977-2012 period, this article shows that dealignment has halted during the last decade amongst older and better educated West German voters, and that party identification is now more widespread than it was in the 1990s in the east. For voters who identified with one of the relevant parties at the time of the 2013 election, their vote choice was more or less a foregone conclusion, as candidates and issues played only a minor role for this group. A detailed analysis of leftist voters shows that supporters of the Greens, the Left, and the SPD have broadly similar preferences but diverging partisan identities. Even amongst western voters of the Left, most respondents claim to be identifiers. This suggests that the fragmentation of the left is entrenched, and that ‘agenda’ policies have triggered a realignment.

@Article{arzheimer-2017b, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {Another Dog that did not Bark? Less Dealignment and More Partisanship in the 2013 Bundestag Election}, journal = {German Politics}, keywords = {gp-e, attitudes-e}, year = 2017, pages = {49-64}, volume = {26}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/paper/another-dog-that-didnt-bark-partisan-de-alignment-and-voting-in-the-2013-election/}, number = {1}, abstract = {Using new data for the 1977-2012 period, this article shows that dealignment has halted during the last decade amongst older and better educated West German voters, and that party identification is now more widespread than it was in the 1990s in the east. For voters who identified with one of the relevant parties at the time of the 2013 election, their vote choice was more or less a foregone conclusion, as candidates and issues played only a minor role for this group. A detailed analysis of leftist voters shows that supporters of the Greens, the Left, and the SPD have broadly similar preferences but diverging partisan identities. Even amongst western voters of the Left, most respondents claim to be identifiers. This suggests that the fragmentation of the left is entrenched, and that ‘agenda’ policies have triggered a realignment.}, doi = {10.1080/09644008.2016.1266481}, }

Original 2015 post

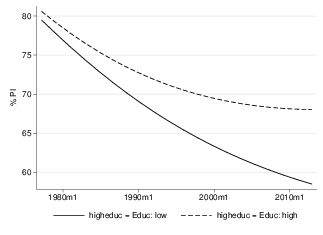

Last week, I showed you that partisan dealignment in the Western federal states of Germany has slowed down considerably, and essentially came to a standstill during the last decade. But what are the mechanisms behind this trend? I think that one part of the puzzle is the changing role of formal education.

More Formal Education, Less Party Identification?

In the quaint olde world that was Western Germany, formal education and party identification were supposed to be negatively correlated. One reason for that is simple: Voters with higher levels of formal education were less likely to belong to the working class, and less likely to be frequent churchgoers, hence less likely to belong to the respective core constituencies of the two major parties. A second, more intriguing reason is cognitive mobilisation (Dalton 1984). In this view, party identification serves as a heuristic that reduces the cognitive costs of processing political information. Educated, more interested voters, however, face lower cognitive costs and have therefore fewer incentives to develop partisan attachments. Thus, the rising level of educational attainment should undermine partisanship.

Formal Education and Party Identification: A Changing Relationship

More recently, doubts have been raised about the merits of cognitive mobilisation theory, as there is growing evidence that politically sophisticated voters are more, not less likely to be partisans (Albright 2009, Dassonneville et al. 2012). One possible reason for this is the changing role of educational attainment in Germany. Three or even two decades ago, the vast majority of voters had spent ten years or less in school, but for the younger generations, the Abitur is slowly becoming the norm. Low levels of attainment are now increasingly associated with political and social marginalisation.

At any rate, education has an increasingly positive effect in my individual-level model of partisanship in the Western states for the 1977-2012 period. Controlling for age group, time and a lot of nifty interactions, it would seem that in recent years, dealignment has mostly been confined to the lower-education strata, while in the growing upper educational echelons, the downward trend in partisanship has petered out for the time being, slowing down the overall decline.

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

RT @kai_arzheimer: Spread of Education Slows Down Partisan Dealignment in Germany

https://t.co/jdKXBTeOJI https://t.co/3yBAHs5b1b

Blog by @kai_arzheimer: “Spread of #Education Slows Down Partisan #Dealignment in Germany” http://t.co/LPp9iKgGPD cc @Vivi_Katharina #PolSci

RT @kai_arzheimer: Partisan Dealignment in #Germany by levels of formal education http://t.co/kqDnyBErzc http://t.co/nKRnunvEAE

RT @kai_arzheimer: Partisan Dealignment in #Germany by levels of formal education http://t.co/kqDnyBErzc http://t.co/nKRnunvEAE

RT @kai_arzheimer: Partisan Dealignment in #Germany by levels of formal education http://t.co/kqDnyBErzc http://t.co/nKRnunvEAE

RT @kai_arzheimer: Partisan Dealignment in #Germany by levels of formal education http://t.co/kqDnyBErzc http://t.co/nKRnunvEAE

RT @kai_arzheimer: Partisan Dealignment in #Germany by levels of formal education http://t.co/kqDnyBErzc http://t.co/nKRnunvEAE

RT @kai_arzheimer: New blog: #Education slows down partisan dealignment in #Germany

http://t.co/bHQe3WQgSn http://t.co/1qfyhBqTdg