Introduction

With the renewed Russian attack on Ukraine in February 2022, the relationship between the “Alternative for Germany” and Russia came into the focus of a wider public for the first time. In fact, however, there have been numerous relationships between the party and Russia almost from the beginning. Analytically, three different dimensions can be distinguished:

- ideology and substantive positions

- election campaign and electoral support

- Personal relationships and dependencies.

Even though these three aspects are closely related in terms of content, they will initially be considered separately in the following.

Ideology and substantive positions

Although most radical right-wing populist parties can be considered admirers of Putin’s Russia (Ivaldi and Zankina 2023) , top AfD politicians rarely evaluate Russian politics, Vladimir Putin’s system of rule, or the country’s culture and history in general terms. Such general statements are also largely absent from the party’s basic program and election manifestos. If at all, general assessments can only be made of individual politicians in the party who have close personal ties to Russia or the Kremlin. In this respect, it is difficult to reconstruct an ideological “image of Russia” in the narrower sense that could be directly attributed to the AfD.

- Arzheimer, Kai. “Im Osten nichts Neues? Die elektorale Unterstützung von AfD und Linkspartei in den alten und neuen Bundesländern bei der Bundestagswahl 2021.” Wahlen und Wähler – Analysen zur Bundestagwahl 2021. Eds. Schoen, Harald and Bernhard Weßels. Wiesbaden: Springer, 2024. 139-178. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-42694-1_6

[BibTeX] [Download PDF] [HTML]@InCollection{arzheimer-2023c, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {Im Osten nichts Neues? Die elektorale Unterstützung von AfD und Linkspartei in den alten und neuen Bundesländern bei der Bundestagswahl 2021}, booktitle = {Wahlen und Wähler - Analysen zur Bundestagwahl 2021}, publisher = {Springer}, year = 2024, editor = {Schoen, Harald and Weßels, Bernhard}, address = {Wiesbaden}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/bundestagswahl-2021-ostdeutschland-linkspartei-afd.pdf}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/bundestagswahl-2021-ostdeutschland-linkspartei-afd/}, dateadded = {14-11-2022}, doi = {10.1007/978-3-658-42694-1_6}, pages = {139-178} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “Identification with an anti-system party undermines diffuse political support: The case of Alternative for Germany and trust in the Federal Constitutional Court.” Party Politics 31.3 (2024): 397-409. doi:10.1177/13540688241237493

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [HTML]The rise of the far right is increasingly raising the question of whether partisanship can have negative consequences for democracy. While issues such as partisan bias and affective polarization have been extensively researched, little is known about the relationship between identification with anti-system parties and diffuse system support. I address this gap by introducing a novel indicator and utilising the GESIS panel dataset, which tracks the rise of a new party, “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) from 2013, when the party was founded, to 2017, when the AfD, now transformed into a right-wing populist and anti-system party, entered the federal parliament for the first time. Employing a panel fixed effects design, I demonstrate that identification with “Alternative for Germany” reduces trust in the Federal Constitutional Court by a considerable margin. These findings are robust across various alternative specifications, suggesting that the effects of anti-system party identification should not be dismissed.

@Article{arzheimer-2024, author = {Kai Arzheimer}, title = {Identification with an anti-system party undermines diffuse political support: The case of Alternative for Germany and trust in the Federal Constitutional Court}, journal = {Party Politics}, year = 2024, volume = 31, number = 3, pages = {397-409}, keywords = {EuroReX, AfD}, abstract = {The rise of the far right is increasingly raising the question of whether partisanship can have negative consequences for democracy. While issues such as partisan bias and affective polarization have been extensively researched, little is known about the relationship between identification with anti-system parties and diffuse system support. I address this gap by introducing a novel indicator and utilising the GESIS panel dataset, which tracks the rise of a new party, "Alternative for Germany" (AfD) from 2013, when the party was founded, to 2017, when the AfD, now transformed into a right-wing populist and anti-system party, entered the federal parliament for the first time. Employing a panel fixed effects design, I demonstrate that identification with "Alternative for Germany" reduces trust in the Federal Constitutional Court by a considerable margin. These findings are robust across various alternative specifications, suggesting that the effects of anti-system party identification should not be dismissed.}, doi = {10.1177/13540688241237493}, pdf = {https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/13540688241237493}, html = {https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/13540688241237493} } - Arzheimer, Kai, Theresa Bernemann, and Timo Sprang. “Oppression of Catholics in Prussia Does Not Explain Spatial Differences in Support for the Radical Right in Germany. A Critique of Haffert (2022).” Electoral Studies 89 (2024): 102789. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2024.102789

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [HTML]A growing literature links contemporary far-right mobilization to the “legacies” of events in the distant past, but often, the effects are small, and their estimates appear to rely on problematic assumptions. We re-analyse Haffert’s (2022) study, a key example of this strand of research. Haffert claims that historical political oppression of Catholics in Prussia moderates support for the radical right AfD party among Catholics in contemporary Germany. While the argument itself has intellectual merit, we identify some severe limitations in the empirical strategy. Retesting the study’s cross-level interaction hypothesis using more suitable multi-level data and a more appropriate statistical model, we find a modest overall difference in AfD support between formerly Prussian and non-Prussian territories. However, this difference is unrelated to individual Catholic religion or to the contextual presence of Catholics. This contradicts the oppression hypothesis. Our study thus provides another counterpoint to the claim that historical events have strong and long-lasting effects on contemporary support for the radical right. We conclude that simpler explanations for variations in radical right support should be exhausted before resorting to history.

@Article{arzheimer-bernemann-sprang-2024, author = {Arzheimer, Kai and Bernemann, Theresa and Sprang, Timo}, title = {Oppression of Catholics in Prussia Does Not Explain Spatial Differences in Support for the Radical Right in Germany. A Critique of Haffert (2022)}, journal = {Electoral Studies}, year = 2024, volume = 89, pages = 102789, abstract = {A growing literature links contemporary far-right mobilization to the "legacies" of events in the distant past, but often, the effects are small, and their estimates appear to rely on problematic assumptions. We re-analyse Haffert's (2022) study, a key example of this strand of research. Haffert claims that historical political oppression of Catholics in Prussia moderates support for the radical right AfD party among Catholics in contemporary Germany. While the argument itself has intellectual merit, we identify some severe limitations in the empirical strategy. Retesting the study's cross-level interaction hypothesis using more suitable multi-level data and a more appropriate statistical model, we find a modest overall difference in AfD support between formerly Prussian and non-Prussian territories. However, this difference is unrelated to individual Catholic religion or to the contextual presence of Catholics. This contradicts the oppression hypothesis. Our study thus provides another counterpoint to the claim that historical events have strong and long-lasting effects on contemporary support for the radical right. We conclude that simpler explanations for variations in radical right support should be exhausted before resorting to history.}, html = {https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261379424000477}, pdf = {https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261379424000477/pdfft?md5=8b0c75faf974eb845135c7c1e0f41c14&pid=1-s2.0-S0261379424000477-main.pdf}, doi = {10.1016/j.electstud.2024.102789} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “Die AfD und Russland.” Jahrbuch Extremismus und Demokratie. Eds. Backes, Uwe, Alexander Gallus, Eckhard Jesse, and Tom Thieme. Vol. 36. Nomos, 2024. 207-220.

[BibTeX] [HTML]@InCollection{arzheimer-2024b, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {Die AfD und Russland}, booktitle = {Jahrbuch Extremismus und Demokratie}, pages = {207-220}, publisher = {Nomos}, year = 2024, editor = {Uwe Backes and Alexander Gallus and Eckhard Jesse and Tom Thieme}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-russland-verbindung/}, volume = 36, dateadded = {25-06-2024} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “The Electoral Breakthrough of the AfD and the East-West Divide In German Politics.” Contemporary Germany and the Fourth Wave of Far-Right Politics: From the Streets to Parliament. Ed. Weisskircher, Manès. London: Routledge, 2023. 140-158.

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [HTML]The radical right became a relevant party family in most west European polities in the 1990s and early 2000s, but Germany was a negative outlier up until very recently. Right-wing mobilisation success remained confinded to the local and regional level, as previous far-right parties never managed to escape from the shadow of “Grandpa’s Fascism”. This only changed with the rise, electoral breakthrough, and transformation of “Alternative for Germany” (AfD), which quickly became the dominant far-right actor. Germany’s “new” eastern states were crucial for the AfD’s ascendancy. In the east, the AfD began to experiment with nativist messages as early as 2014. Their electoral breakthroughs in the state elections of this year helped sustain the party through the wilderness year of 2015 and provided personel, ressources, and a template for the AfD’s transformation. Since its inception, support for the AfD in the east has been at least twice as high as in the west. This can be fully explained by substantively higher levels of nativist attitudes in the eastern population. As all alleged causes of this nativism are structural, the eastern states seem set to remain a stronghold for the far right in the medium- to long-term.

@InCollection{arzheimer-2021, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {The Electoral Breakthrough of the AfD and the East-West Divide In German Politics}, booktitle = {Contemporary Germany and the Fourth Wave of Far-Right Politics: From the Streets to Parliament}, publisher = {Routledge}, editor = {Weisskircher, Manès}, year = 2023, pages = {140-158}, address = {London}, abstract = {The radical right became a relevant party family in most west European polities in the 1990s and early 2000s, but Germany was a negative outlier up until very recently. Right-wing mobilisation success remained confinded to the local and regional level, as previous far-right parties never managed to escape from the shadow of “Grandpa’s Fascism”. This only changed with the rise, electoral breakthrough, and transformation of “Alternative for Germany” (AfD), which quickly became the dominant far-right actor. Germany’s “new” eastern states were crucial for the AfD’s ascendancy. In the east, the AfD began to experiment with nativist messages as early as 2014. Their electoral breakthroughs in the state elections of this year helped sustain the party through the wilderness year of 2015 and provided personel, ressources, and a template for the AfD’s transformation. Since its inception, support for the AfD in the east has been at least twice as high as in the west. This can be fully explained by substantively higher levels of nativist attitudes in the eastern population. As all alleged causes of this nativism are structural, the eastern states seem set to remain a stronghold for the far right in the medium- to long-term.}, keywords = {eurorex,afd}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/paper/afd-east-west-cleavage-breakthrough/}, dateadded = {12-04-2021} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “To Russia with love? German populist actors’ positions vis-a-vis the Kremlin.” The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe. Eds. Ivaldi, Gilles and Emilia Zankina. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), 2023. 156-167. doi:10.55271/rp0020

[BibTeX] [Abstract]Russia’s fresh attack on Ukraine and its many international and national repercussions have helped to revive the fortunes of Germany’s main radical right-wing populist party ‘Alternative for Germany’ (AfD). Worries about traditional industries, energy prices, Germany’s involvement in the war and hundreds of thousands of refugees arriving in Germany seem to have contributed to a modest rise in the polls after a long period of stagnation. However, the situation is more complicated for the AfD than it would appear at first glance. While many party leaders and the rank-and-file have long held sympathies for Putin and more generally for Russia, support for Ukraine is still strong amongst the German public, even if there is some disagreement about the right means and the acceptable costs. At least some AfD voters are appalled by the levels of Russian violence against civilians, and the party’s electorate is divided as to the right course of action. To complicate matters, like on many other issues, there is a gap in opinion between Germany’s formerly communist federal states in the East and the western half of the country. As a result, the AfD leadership needs to tread carefully or risk alienating party members and voters in the more populous western states. Beyond the AfD, the current and future consequences of the war have galvanised the larger far-right movement, particularly in the East. Moreover, they have led to further tensions in the left-wing populist “Linke” (left) party, which is traditionally pacifist and highly sceptical of NATO. The majority of the party tries to square commitment to these principles with solidarity with the victims of Russian aggression. A small but very visible faction, however, shows at least a degree of support for Russia and blames NATO and the US for the war.

@InCollection{arzheimer-2023e, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {To Russia with love? German populist actors' positions vis-a-vis the Kremlin}, booktitle = {The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe}, publisher = {European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS)}, year = 2023, editor = {Ivaldi, Gilles and Zankina, Emilia}, pages = {156-167}, address = {Brussels}, abstract = {Russia's fresh attack on Ukraine and its many international and national repercussions have helped to revive the fortunes of Germany's main radical right-wing populist party 'Alternative for Germany' (AfD). Worries about traditional industries, energy prices, Germany's involvement in the war and hundreds of thousands of refugees arriving in Germany seem to have contributed to a modest rise in the polls after a long period of stagnation. However, the situation is more complicated for the AfD than it would appear at first glance. While many party leaders and the rank-and-file have long held sympathies for Putin and more generally for Russia, support for Ukraine is still strong amongst the German public, even if there is some disagreement about the right means and the acceptable costs. At least some AfD voters are appalled by the levels of Russian violence against civilians, and the party's electorate is divided as to the right course of action. To complicate matters, like on many other issues, there is a gap in opinion between Germany's formerly communist federal states in the East and the western half of the country. As a result, the AfD leadership needs to tread carefully or risk alienating party members and voters in the more populous western states. Beyond the AfD, the current and future consequences of the war have galvanised the larger far-right movement, particularly in the East. Moreover, they have led to further tensions in the left-wing populist "Linke" (left) party, which is traditionally pacifist and highly sceptical of NATO. The majority of the party tries to square commitment to these principles with solidarity with the victims of Russian aggression. A small but very visible faction, however, shows at least a degree of support for Russia and blames NATO and the US for the war.}, doi = {10.55271/rp0020} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “Regionalvertretungswechsel von links nach rechts? Die Wahl von Alternative für Deutschland und Linkspartei in Ost-West-Perspektive.” Wahlen und Wähler – Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagwahl 2017. Eds. Schoen, Harald and Bernhard Wessels. Wiesbaden: Springer, 2021. 61-80. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-33582-3_4

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML] [DATA]Bei der Bundestagswahl 2017 zeigten sich wiedereinmal dramatische Ost-West-Unterschiede. Diese gingen vor allem auf den überdurchschnittlichen Erfolg von AfD und LINKE in den neuen Ländenr zurück. Die AfD ist vor allem in Thüringen und Sachsen besonders stark , die LINKE in Berlin, aber auch in den Stadtstaaten Bremen und Hamburg sowie in einigen westdeutschen Großstädten. Die Wahlentscheidung zugunsten beider Parteien wird sehr stark von Einstellungen zum Sozialstaat (im Falle der Linkspartei) sowie zur Zuwanderung (im Falle der AfD) bestimmt. Beide Parteien profitieren überdies von einem Gefühl der Unzufriedenheit mit dem Funktionieren der Demokratie. Sobald für diese Faktoren kontrolliert wird, zeigt sich, dass die AfD keinen davon unabhängigen “Ost-Bonus” genießt. Zugleich deuten die Modellschätzungen auf substantielle Einflüsse auf der Wahlkreisebene hin. Im Falle der Linkspartei bleibt dagegen ein substantieller Effekt des Befragungsgebietes erhalten, selbst wenn für die Einstellungen kontrolliert wird. Signifikante Differenzen zwischen den Wahlkreisen gibt es hier nicht.

@InCollection{arzheimer-2019, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {Regionalvertretungswechsel von links nach rechts? Die Wahl von Alternative für Deutschland und Linkspartei in Ost-West-Perspektive}, booktitle = {Wahlen und Wähler - Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagwahl 2017}, publisher = {Springer}, year = 2021, data = {https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/Q2M1AS}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-linkspartei-ostdeutschland/}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-linkspartei-ostdeutschland.pdf}, doi = {10.1007/978-3-658-33582-3_4}, editor = {Schoen, Harald and Wessels, Bernhard}, pages = {61-80}, abstract = {Bei der Bundestagswahl 2017 zeigten sich wiedereinmal dramatische Ost-West-Unterschiede. Diese gingen vor allem auf den überdurchschnittlichen Erfolg von AfD und LINKE in den neuen Ländenr zurück. Die AfD ist vor allem in Thüringen und Sachsen besonders stark , die LINKE in Berlin, aber auch in den Stadtstaaten Bremen und Hamburg sowie in einigen westdeutschen Großstädten. Die Wahlentscheidung zugunsten beider Parteien wird sehr stark von Einstellungen zum Sozialstaat (im Falle der Linkspartei) sowie zur Zuwanderung (im Falle der AfD) bestimmt. Beide Parteien profitieren überdies von einem Gefühl der Unzufriedenheit mit dem Funktionieren der Demokratie. Sobald für diese Faktoren kontrolliert wird, zeigt sich, dass die AfD keinen davon unabhängigen "Ost-Bonus" genießt. Zugleich deuten die Modellschätzungen auf substantielle Einflüsse auf der Wahlkreisebene hin. Im Falle der Linkspartei bleibt dagegen ein substantieller Effekt des Befragungsgebietes erhalten, selbst wenn für die Einstellungen kontrolliert wird. Signifikante Differenzen zwischen den Wahlkreisen gibt es hier nicht.}, address = {Wiesbaden}, dateadded = {01-04-2019} } - Arzheimer, Kai and Carl Berning. “How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013-2017.” Electoral Studies 60 (2019): online first. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML]Until 2017, Germany was an exception to the success of radical right parties in postwar Europe. We provide new evidence for the transformation of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) to a radical right party drawing upon social media data. Further, we demonstrate that the AfD’s electorate now matches the radical right template of other countries and that its trajectory mirrors the ideological shift of the party. Using data from the 2013 to 2017 series of German Longitudinal Elections Study (GLES) tracking polls, we employ multilevel modeling to test our argument on support for the AfD. We find the AfD’s support now resembles the image of European radical right voters. Specifically, general right-wing views and negative attitudes towards immigration have become the main motivation to vote for the AfD. This, together with the increased salience of immigration and the AfD’s new ideological profile, explains the party’s rise.

@Article{arzheimer-berning-2019, author = {Arzheimer, Kai and Berning, Carl}, title = {How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013-2017}, journal = {Electoral Studies}, year = 2019, doi = {10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004}, volume = {60}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/alternative-for-germany-voters}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/alternative-for-germany-party-voters-transformation.pdf}, pages = {online first}, abstract = {Until 2017, Germany was an exception to the success of radical right parties in postwar Europe. We provide new evidence for the transformation of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) to a radical right party drawing upon social media data. Further, we demonstrate that the AfD's electorate now matches the radical right template of other countries and that its trajectory mirrors the ideological shift of the party. Using data from the 2013 to 2017 series of German Longitudinal Elections Study (GLES) tracking polls, we employ multilevel modeling to test our argument on support for the AfD. We find the AfD's support now resembles the image of European radical right voters. Specifically, general right-wing views and negative attitudes towards immigration have become the main motivation to vote for the AfD. This, together with the increased salience of immigration and the AfD's new ideological profile, explains the party's rise.}, dateadded = {01-04-2019} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “‘Don’t mention the war!’ How populist right-wing radicalism became (almost) normal in Germany.” Journal of Common Market Studies 57.S1 (2019): 90-102. doi:10.1111/jcms.12920

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML]After decades of false dawns, the “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) is the first radical right-wing populist party to establish a national presence in Germany. Their rise was possible because they started out as soft-eurosceptic and radicalised only gradually. The presence of the AfD had relatively little impact on public discourses but has thoroughly affected the way German parliaments operate: so far, the cordon sanitaire around the party holds. However, the AfD has considerable blackmailing potential, especially in the eastern states. In the medium run, this will make German politics even more inflexible and inward looking than it already is.

@Article{arzheimer-2019c, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {'Don't mention the war!' How populist right-wing radicalism became (almost) normal in Germany}, journal = {Journal of Common Market Studies}, year = 2019, abstract = {After decades of false dawns, the "Alternative for Germany" (AfD) is the first radical right-wing populist party to establish a national presence in Germany. Their rise was possible because they started out as soft-eurosceptic and radicalised only gradually. The presence of the AfD had relatively little impact on public discourses but has thoroughly affected the way German parliaments operate: so far, the cordon sanitaire around the party holds. However, the AfD has considerable blackmailing potential, especially in the eastern states. In the medium run, this will make German politics even more inflexible and inward looking than it already is.}, volume = {57}, pages = {90-102}, number = {S1}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/right-wing-populism-germany-normalisation}, dateadded = {27-05-2019}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-normalisation-right-wing-populism-germany.pdf}, doi = {10.1111/jcms.12920}, keywords = {EuroReX, AfD} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “The AfD: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?.” West European Politics 38 (2015): 535–556. doi:10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML] [DATA]Within less than two years of being founded by disgruntled members of the governing CDU, the newly-formed Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has already performed extraordinary well in the 2013 General election, the 2014 EP election, and a string of state elections. Highly unusually by German standards, it campaigned for an end to all efforts to save the Euro and argued for a re-configuration of Germany’s foreign policy. This seems to chime with the recent surge in far right voting in Western Europe, and the AfD was subsequently described as right-wing populist and europhobe. On the basis of the party’s manifesto and of hundreds of statements the party has posted on the internet, this article demonstrates that the AfD does indeed occupy a position at the far-right of the German party system, but it is currently neither populist nor does it belong to the family of Radical Right parties. Moreover, its stance on European Integration is more nuanced than expected and should best be classified as soft eurosceptic.

@Article{arzheimer-2015, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {The AfD: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?}, journal = {West European Politics}, year = 2015, volume = 38, pages = {535--556}, doi = {10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230}, keywords = {gp-e, cp, eurorex}, abstract = {Within less than two years of being founded by disgruntled members of the governing CDU, the newly-formed Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has already performed extraordinary well in the 2013 General election, the 2014 EP election, and a string of state elections. Highly unusually by German standards, it campaigned for an end to all efforts to save the Euro and argued for a re-configuration of Germany's foreign policy. This seems to chime with the recent surge in far right voting in Western Europe, and the AfD was subsequently described as right-wing populist and europhobe. On the basis of the party's manifesto and of hundreds of statements the party has posted on the internet, this article demonstrates that the AfD does indeed occupy a position at the far-right of the German party system, but it is currently neither populist nor does it belong to the family of Radical Right parties. Moreover, its stance on European Integration is more nuanced than expected and should best be classified as soft eurosceptic. }, data = {https://hdl.handle.net/10.7910/DVN/28755}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-right-wing-populist-eurosceptic-germany}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-right-wing-populist-eurosceptic-germany.pdf} }

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

However, the AfD has certainly taken a consistent position on Russia over a long period of time. These positions, in turn, fit seamlessly into a picture of foreign policy that is characterized by thinking in terms of spheres of influence, distrust of the EU and the USA, and an orientation towards alleged German (economic) interests (Shein and Ryzhkin 2024; Ostermann and Stahl 2022; Greene 2023) . The AfD thus stands in a tradition of foreign policy thinking in Germany that goes back to the 19th century and was revived in the 1990s (Klinke 2018) .

This is especially, but not only, true for the right-wing fringe of the political spectrum. Although the Nazis justified their crimes in the East with the alleged racial inferiority of the Slavic peoples, German right-wing extremists began to network with like-minded actors in Central and Eastern Europe soon after 1990 (Maegerle 2009) . Among the Eastern European states, Russia exerted a particular attraction for the far right in Germany because it was seen as a rival to US hegemony and as an autocratic counter-project to liberal democracy. Although there were also contacts with far-right actors in Ukraine, Russia became the main focus at the latest with the annexation of Crimea in 2014. For example, immediately after the annexation, the anti-Islam movement Pegida included a demand for “an end to anti-Russian warmongering” (meaning the very restrained criticism of the annexation in Germany) in its manifesto (Jennerjahn 2016, 539) .

The AfD took a similar position back then. In 2013, the then Brandenburg state chairman Alexander Gauland , still one of the most influential politicians within the AfD, had already shown great understanding for Russian claims to Ukraine in a foreign policy position paper often referred to as the “Bismarck Paper”, and equated the “detachment of holy Kiev” with the “separation of Aachen or Cologne” from Germany (Lachmann 2013) . This was not an isolated opinion. A content analysis of the AfD website in 2014 – a central medium for the party at the time – showed an unusually high level of support for Russia and mistrust of the USA in the German context (Arzheimer 2015, 548) .

In April of the same year, Gauland compared a possible division of Ukraine with the peaceful dissolution of Czechoslovakia (FAZ 2014) . Immediately after the annexation of Crimea by Russia in March, the AfD federal party conference in Erfurt, with Gauland’s support, had already passed a resolution rejecting sanctions against Russia and calling the government in Kiev illegitimate (Litschko 2014) . When Bernd Lucke and other AfD MPs nevertheless voted in favor of an EU sanctions package in the European Parliament in August 2014, Gauland threatened to resign before the state elections in September (Patton 2014, 6–7) .

In its election manifesto for the 2017 federal election, the AfD called for a relaxation of relations with Russia, an end to the (very limited) sanctions that had been imposed after the annexation, a general deepening of economic relations with Russia and even the inclusion of Russia in an unspecified collective security structure. The next and the next sentence then state: “Relations with Turkey, on the other hand, are shaken and must be restructured. Culturally, Turkey does not belong to Europe. (…) Turkey’s membership in NATO must be ended…” (Alternative for Germany 2017a) . In other words: In its own perception, the AfD was closer to being a potential enemy of NATO than to being a NATO member.

Calls for an end to sanctions against Russia can be found even earlier in the manifestos for the state elections in Baden-Württemberg and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (both in 2016) and were taken up again in the state election manifestos for Saxony and Thuringia (both in 2019), among others. The latter program also calls for an expansion of electricity generation from natural gas and explicitly names Russia (along with Norway and the Netherlands) as a particularly reliable supplier. This is where pro-Russian positions and the insistence on fossil forms of energy production come together – a pattern that would intensify after the Russian attack in February 2022.

After entering the Bundestag in September 2017, the AfD repeated its call for an end to sanctions in the plenary session. It criticized the expulsion of Russian diplomats from Great Britain after the poison attack in Salisbury and celebrated Putin’s success in the unfree Russian presidential election of 2018. In the same year, it bombarded the federal government with a series of written inquiries about German-Russian relations and accused the new Federal Foreign Minister Heiko Maas of wanting to drive Germany into a war with anti-Russian rhetoric on behalf of and in the interests of foreign organizations (the Atlantic Bridge and the German Marshal Fund were mentioned) (Wood 2021, 779) . The parallels to common conspiracy theories, but also to the Russian law on “foreign agents” are obvious.

A simple quantitative analysis of the speeches made by AfD MPs in the 19th legislative period (2017-2021) is also revealing. With 349 mentions, Russia was by far the most frequently mentioned country by the AfD, along with China and the USA (360 and 440 respectively). If one examines in a second step which words appear more frequently than by chance in the context of the country name (collocations), the strongest association by far is for the term “sanctions”, followed by the names of the two superpowers China and the USA and the prepositions “with” and “against”. In a period in which the Russia-Ukraine conflict received comparatively little attention from the wider public, the AfD vehemently campaigned for the lifting of the (already quite weak) sanctions against Russia and called for closer economic and political relations with Russia.>2

In the first Bundestag debate after the attack in February 2022, the party was initially somewhat more cautious. In a statement for his parliamentary group, MP Matthias Moosdorf called the war a “tragedy” and demanded that Russia return to the negotiating table. At the same time, however, he claimed that there was systematic persecution of “people of Russian origin” in Ukraine, described a Russian victory as inevitable and proposed referendums on the cession of Crimea and territories in eastern Ukraine. The AfD continued to reject sanctions against Russia and military aid to Ukraine (see “Plenary Protocol 20/20” 2022, 1435) .

In June 2022, the parliamentary group published a paper that took a similar position. It described Russia’s war of aggression as a violation of international law. As a consequence, however, it did not call for a withdrawal of Russian troops, but rather for a ceasefire and the deployment of “a United Nations and OSCE peacekeeping force to Ukraine.” At the same time, the AfD renewed its support for the Nord Stream II project because it makes a significant “contribution to a reliable, secure and affordable energy supply for Germany” (AfD parliamentary group in the Bundestag 2022) . At that time, Russia had already reduced deliveries through the Nord Stream I pipeline by 60 percent, only to end it completely three months later.

In late summer 2022, the AfD tightened its course again and now openly declared that it wanted to make the population’s concerns about energy supplies, the economic situation and the threat of war a campaign theme (Nefzger 2022; Sternberg 2022) . A few weeks later, co-chair Weidel showed what this could look like. In an almost incomprehensible reversal of the actual situation, she explained in an interview with Deutschlandfunk that the real loser of the conflict was neither Russia nor Ukraine, but rather Germany, because this was in fact an “economic war against Germany”. Western support for “Ukrainian maximum demands” [for the restoration of control over its territory] was “unreflective”, and German aid to Ukraine should therefore be rejected accordingly. The primary goal of German policy must rather be the supply of cheap Russian natural gas. A division of Ukraine must be accepted in favor of German economic interests (Deutschlandfunk 2022) . A few weeks later, Weidel’s co-chair Chrupalla reiterated this position in an interview with ZDF: “Some American presidents” had been war criminals, but Putin was not a war criminal for him because he was not in a position to judge his actions (Today 2022) .

The party maintained this general line in the following months. In February 2023, one year after the latest attack on Ukraine, the AfD parliamentary group drafted a motion for a German “peace initiative”. In addition to the idea of an OSCE force for the territories occupied by Russia, this motion contained the demand that “political, military and financial support for Ukraine should be linked to Kyiv’s willingness to negotiate serious peace talks”, while Russia should only be “demanded to be willing to talk” (AfD parliamentary group in the Bundestag 2023a, 3) . The intensive discussion of sanctions, which was already quantitatively shown above for the 19th Bundestag, has also been and will continue in the current legislative period. Similar to Weidel’s interview, these are always linked to losses in prosperity in Germany.

This position was formulated and codified in the programme for the 2024 European elections, which was adopted in summer 2023. It states:

“For decades, Russia has been a reliable supplier and guarantor of affordable energy supplies, which, due to our energy-intensive industry, represents the Achilles heel of the German economy. Restoring uninterrupted trade with Russia includes the immediate lifting of economic sanctions against Russia and the repair of the Nord Stream pipelines. Germany’s relations with the Eurasian Economic Union should be expanded.” (Alternative for Germany 2023, 29)

The AfD also blames the USA for the weakening of economic relations and thus indirectly for the Russia-Ukraine conflict, even if this is formulated in a somewhat cryptic way:

“We reject any dominance of non-European major powers in European foreign and security policy. The states of Europe are thus drawn into conflicts that are not theirs and are diametrically opposed to their natural interests – fruitful trade relations in the European-Asian region.” (Alternative for Germany 2023, 8)

And:

“The Nord Stream project is of outstanding importance for the European energy supply and cannot be replaced without far-reaching economic problems. Germany must not allow itself to be drawn into conflicts by the USA’s decisions that set the course for other powers.” (Alternative for Germany 2023, 29)

Against this background, it is hardly surprising that the AfD parliamentary group in the Bundestag submitted a motion for a resolution to repair the Nord Stream pipelines in October 2023 (AfD parliamentary group in the Bundestag 2023d) . A look at other parliamentary initiatives by the AfD is also revealing. These were directed against the confiscation of Russian cars when entering Germany (AfD parliamentary group in the Bundestag 2023c) , against the expulsion of Russian diplomats (AfD parliamentary group in the Bundestag 2023b) , against considerations at EU level on the confiscation of Russian state assets (AfD parliamentary group in the Bundestag 2024b) , and against obstacles to the exchange of so-called “deposit receipts” for Russian shares (AfD parliamentary group in the Bundestag 2024a) . The AfD’s pro-Russian line reached a temporary high point on June 11, 2024, when the parliamentary group leadership called on its MPs to stay away from a speech by Ukrainian President Zelenskyj in the Bundestag and denounced him as a “war and begging president” who stood in the way of a peace agreement (AfD parliamentary group in the Bundestag 2024c) . Only four of the AfD’s 77 MPs attended the meeting and applauded Zelenskyj.

Election campaign and electoral support

Since 2013, rejection of migration and migrants has become the central motive for voting for the AfD and is at the heart of the party’s ideology (Arzheimer and Berning 2019) . Nevertheless, there is a special group of immigrants who are more positive than average towards the AfD and are also specifically addressed by it: the approximately 2.5 million people who came to Germany from the territory of the former Soviet Union after the end of the Cold War. The vast majority of them are ethnic Germans (“Russian Germans”). Nevertheless, some members of this group are not well integrated and get at least some of their political information from Russian or Russian-language media (Sablina 2021, 362) .

Although they feel German and their ancestors were persecuted in the Soviet Union because of their ethnicity, Russian Germans are also often victims of xenophobia and discrimination. This is also why many members of this group reacted very negatively to the large refugee movements of 2015/16. These feelings were and are deliberately fueled by state and state-affiliated Russian media (Sablina 2021, 362–63) .

At the same time, the AfD began producing Russian-language posters, brochures and social media content (May 2016) aimed at Russian-Germans in 2016 at the latest. Even the AfD’s basic program, adopted in 2016, is available in Russian translation on the party’s website (Alternative for Germany 2017b) . This was initially hardly noticed by the majority society, but proved to be highly effective: In the 2017 federal election, Russian-Germans in particular who were less well integrated economically and had poor German language skills tended to vote disproportionately often for the AfD (Spies et al. 2022) .

Unfortunately, no comparative data is available for later elections. However, the AfD’s often very good results in places where there are particularly large numbers of Russian Germans (known examples include Pforzheim and Rastatt) indicate that the AfD continues to be particularly successful with this population group.

In the meantime, this special profile of the AfD has become somewhat more visible. In 2017, an “interest group of Russian Germans in the AfD” was founded in Pforzheim, which sought recognition as a party branch in the same year. 3 In the same year, two comparatively prominent and politically active Russian Germans, Anton Friesen and Waldemar Herdt, entered the Bundestag. 4 Both lost their mandates in 2021. Instead, another well-known Russian German , Eugen Schmidt, entered the Bundestag for the AfD, where he is listed as the “State Commissioner for Russian Germans of the AfD North Rhine-Westphalia” and “Commissioner for Russian Germans of the AfD Bundestag parliamentary group” (Deutscher Bundestag 2021) . Friesen , Herdt and Schmidt all have more or less intensive contacts with actors in Russia (see also section 4 ).

For voters outside the Russian-German community, the AfD’s positions on Russia probably played only a minor role until February 2022 – it is no longer possible to determine this with certainty in retrospect. But with the attack at the latest, the importance of the issue changed suddenly: In the second week of March 2022, 67% of all Germans approved of Germany’s very manageable first arms deliveries to Ukraine, while 64% of AfD supporters rejected them . Conversely, only 11% of all respondents at that time rejected general economic sanctions against Russia, compared to 57% of AfD supporters. An oil and gas embargo against Russia was much more controversial, with 39% rejecting it. Among AfD supporters, however, the corresponding figure was 78%.

There are basically three possible explanations for these very strong connections, which are compatible with each other. Either the AfD managed to influence its supporters in Russia’s favor within a very short period of time through appropriate statements. However, since the party, as explained above, represented a comparatively moderate position in parliament at least in the first weeks of the war, this is not very likely. Secondly, it is also conceivable that pro-Russian citizens had already turned increasingly to the party before 2022. However, this is contradicted by the fact that the AfD’s position – as shown above – was constant for many years, but was little known outside the Russian-German community and was overshadowed by its attitudes towards immigration and Islam in the wider public. Thirdly, one can imagine that large parts of the AfD’s supporters had rather latent attitudes towards Russia and Ukraine that were compatible with their general worldview and that these attitudes were activated by the war.

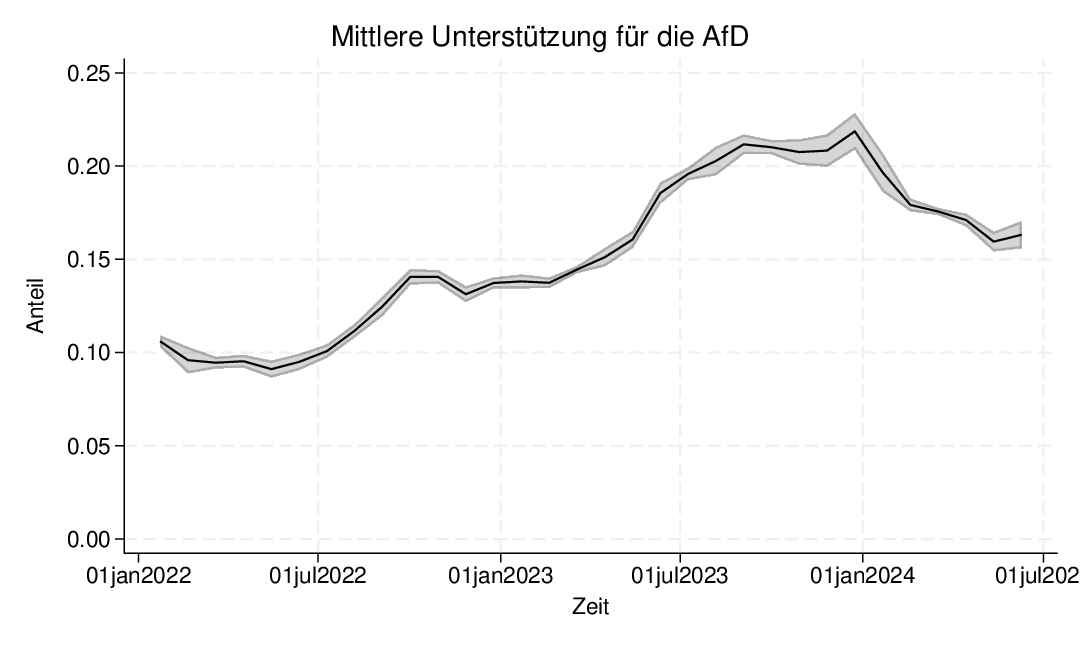

On the other hand, it seems very unlikely that the AfD gained new supporters on a large scale in the first months of the war due to its course, since support for the party stagnated or even declined slightly during this phase (see Figure 1 ) (For the aggregation method, see Arzheimer 2023) . An increase in support from just under ten to just under 15 percent only became apparent in late summer 2022, when, as explained above, Russian gas supplies were stopped and the AfD simultaneously made inflation and energy shortages a campaign issue.

The AfD then experienced a further increase from the early summer of 2023, when a dispute that had been simmering for months between the federal government, states and municipalities over the care of Ukrainian refugees escalated, the Union parties and the FDP increasingly addressed the complex of flight, immigration and integration, and as a result, for the first time since 2017, “migration” again became the most important issue for citizens (Election Research Group nd) . As a result, the AfD’s poll ratings briefly rose to over 20 percent for the first time in the winter of 2023/24. They then fell back to around 15 percent in the wake of the protests against the “Potsdam Meeting”, the founding of the BSW and the scandals surrounding the European candidates Krah and Bystron (see section 4 ).

It should be noted that no nationwide elections were held during this period, so the poll results should primarily be viewed as a reflection of the political mood. However, the AfD’s very good performance by West German standards in the state elections in Bavaria and Hesse on October 8, 2023, as well as the substantial gains in various population groups in the 2024 European elections on June 16, 2024, indicate that the positions on Russia policy as well as the increasingly visible links to right-wing extremism are by no means a deterrent to new groups of voters, but may even mobilize them.

Personal relationships with and dependencies on Russian actors

The Kremlin itself and Russian actors close to the Kremlin have built up a network of contacts with radical right-wing populists in Europe since the 1990s (Ivaldi and Zankina 2023) , which also includes the AfD, which was founded relatively late in comparison to Europe (Gude 2017) . As things stand, there is no evidence that the party as a whole is controlled by Moscow, but there is a strikingly large number of party officials who maintain close and sometimes very questionable contacts with Russia.

Alexander Gauland , then still state chairman in Brandenburg and member of the federal executive board, then party and parliamentary group chairman since 2017 and today honorary chairman of the AfD, had already accepted an invitation to Saint Petersburg in 2015. There he met not only members of the Duma but also the right-wing extremist theorist Alexander Dugin (Jaeger and Schmidt 2017) , who has been systematically maintaining contacts with right-wing radical politicians in the West for almost four decades (Gude 2017) .

Another case even involved the incumbent party leadership. In February 2017, the then chairwoman Frauke Petry and her husband, the MEP and NRW state chairman Marcus Pretzell , together with the federal executive board member Julian Flak , undertook a political trip to Russia. There, the delegation met with Russian politicians, including the chairman of the Duma, Vyacheslav Volodin , and the right-wing extremist politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky (Jaeger and Schmidt 2017) . Research by the FAZ later showed that the hosts had chartered a private jet for this trip. The cost of the flight was around 25,000 euros (FAZ 2018) .

In April 2016, Pretzell had already taken part in a political conference in the Russian-occupied Crimea as an invited guest (Jaeger and Schmidt 2017) . Another participant in this trip was Markus Frohnmaier , then federal chairman of the right-wing extremist “Young Alternative” and a member of the Bundestag since 2017. In 2017, Frohnmaier married a journalist from the pro-government newspaper Izvestia and traveled to Crimea and the occupied territories in eastern Ukraine several times in the following years. Among other things, he was part of a group of AfD politicians who visited Crimea as alleged “international election observers” on the occasion of the 2018 Russian presidential election. At least part of the costs were covered by the Russian Duma at the time (Spiegel 2020) . In 2019, the British BBC presented documents that were supposed to prove that Frohnmaier was “controlled” by the Kremlin (Gatehouse 2019) .

In addition to Frohnmaier, seven other AfD members of the Bundestag, and thus almost a tenth of the parliamentary group, took part in the 2018 “observation mission”: the Russian-German politicians Anton Friesen and Waldemar Herdt mentioned above , as well as Stefan Keuter , Steffen Kotré , Ulrich Oehme and Robby Schlund . All seven continued to attract attention after 2018 by traveling to Russia and the occupied parts of Ukraine, visiting the Russian embassy, appearing in Russian media and spreading Russian propaganda. This also applies to some members of the state parliament. Particularly well-known among these is Gunnar Lindemann , a member of the Berlin House of Representatives who, like Pretzell and Frohnmaier , took part in events in Crimea and other occupied territories and, together with Ulrich Henkel (Bavaria), Olga Pedersen (Hamburg) and Ulrich Singer (Bavaria), took part in a conference followed by “election observation” in September 2021 (Stöber and Becker 2021) . Another group of state parliamentarians — Christian Blex (North Rhine-Westphalia), Hans-Thomas Tillschneider and Thomas Wald (both Saxony-Anhalt) even tried to get to Donbass from Russia in September 2022 (!) to take part in the sham referendum on joining Russia as alleged international observers (Joswig 2022) .

In December 2020 and March 2021, the current party leaders Tino Chrupalla and Alice Weidel traveled to Moscow not as “election observers” but for political talks with the Foreign Ministry, among others (Zeit Online 2021) . Part of Weidel’s delegation was also the Bundestag member and later candidate for the European Parliament Petr Bystron . In March 2024, it became known that Bystron had received payments via the pro-Russian propaganda portal “Voice of Europe” so that he would act and vote in Russia’s interests. Currently (June 2024), the Munich Public Prosecutor’s Office is investigating Bystron on suspicion of bribery and money laundering (Spiegel 2024) . Investigations are also currently underway against two former employees of the MEP and top candidate Maximilian Krah on suspicion of influence from China and Russia respectively. The Dresden Public Prosecutor’s Office has initiated preliminary investigations against Krah himself because of possible connections to both states (Riedel, Flade, and Pittelkow 2024) .

Perhaps the most surprising accusation in connection with Russia and the AfD, however, is being made against Björn Höcke , the Thuringian state chairman and nationally known representative of the nationalist movement . According to information from “Spiegel”, the Russian government had a strategy paper drawn up in 2022 to strengthen the AfD. Passages from it are said to be found almost word for word in a speech that Höcke gave in Gera in October 2022 (Tagesschau nd) . In fact, the speech, which can be heard on Höcke’s YouTube channel, contains numerous talking points that are also spread by Russian propagandists: Russia is being treated unfairly by Western media, politicians and civil society actors out of selfish interest, Germany and Russia are soul mates and therefore natural partners in the fight against the decline in values forced by the USA, participation in the Ukraine war instigated by the USA and the economic embargo is political and economic suicide for Germany, etc. However, it does not seem entirely plausible that Höcke should be dependent on Russian help in formulating such statements.

Conclusion

David F. Patton (Patton 2024) rightly points out that the AfD’s pro-Russian line has triggered and revealed relevant intra-party conflicts. More than two years after the renewed attack on Ukraine, however, these are far below a level that could be dangerous or even unusual for the party.

Rather, the overwhelming majority of the party and its officials support the chosen course. This may also have opportunistic reasons: as shown above, the AfD attracts a considerable proportion of those who are at least skeptical about German support for Ukraine. Even the connections to Russian and Chinese secret services and propaganda operations are viewed as unproblematic by most AfD supporters (Arzheimer 2024) .

At the same time, the above statements have shown that the proximity of large parts of the AfD to Russia dates back to 2013/14. Therefore, one must assume that the party’s Russia policy is not only based on individual and collective considerations of benefit, but also on genuine political convictions.

References

AfD parliamentary group in the Bundestag. 2022. “The impossible war. The AfD parliamentary group has presented a position paper for sustainable peace.”

Fraktion Kompakt. The magazine of the AfD parliamentary group in the Bundestag , June 16–17.

https://afdbundestag.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/fraktionszeitung_ausgabe-5-2022_v7.0.pdf .———. 2023a. “BT Drucksache 20/5551.” The German Bundestag. February 7, 2023.

https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/20/055/2005551.pdf .———. 2023b. “Eugen Schmidt: Diplomatic expulsion further divides Germany and Russia.” April 26, 2023.

https://afdbundestag.de/eugen-schmidt-diplomaten-ausweisung-entzweit-deutschland-und-russland-weiter/ .———. 2023c. “Eugen Schmidt/Kay Gottschalk: Lift sanctions that are not effective.” August 1, 2023.

https://afdbundestag.de/eugen-schmidt-kay-gottschalk-nicht-zielfuehrende-sanktionen-aufheben/ .———. 2023d. “BT Drucksache 20/8744.” The German Bundestag.

https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/20/055/2005551.pdf .———. 2024a. “Kay Gottschalk: Prevent the expropriation of German small shareholders.” February 14, 2024.

https://afdbundestag.de/kay-gottschalk-enteignung-deutscher-kleinaktionaere-verhindern/ .———. 2024b. “BT Drucksache 20/10388.” The German Bundestag.

https://dserver.bundestag.de/btd/20/103/2010388.pdf .———. 2024c. “Alice Weidel/Tino Chrupalla: AfD parliamentary group rejects speech by Selenskyj in the Bundestag.”

https://afdbundestag.de/alice-weidel-tino-chrupalla-afd-fraktion-lehnt-rede-von-selenskyj-im-bundestag-ab/ .Alternative for Germany. 2017a. “Program for Germany. Election program of the Alternative for Germany for the election to the German Bundestag on September 24, 2017.”

https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/2017-06-01_AfD-Bundestagswahlprogramm_Onlinefassung.pdf .———. 2017b. “PROGRAMMA DLYA GERMANII. Programma Al’ternativy Dlya Germanii (AdG).”

https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2017-04-18_afd-grundsatzprogramm_russisch_web.pdf .———. 2017c. “Preliminary application book for the 8th Federal Party Congress in Hanover, December 2nd to December 3rd, 2017.”

https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Vorläufiges_Antragsbuch_01122017_v1.pdf .———. 2023. “Program of the Alternative for Germany for the election to the 10th European Parliament. Adopted at the AfD European election meeting in Magdeburg, July 29 to 30 and August 4 to 6, 2023.”

https://www.afd.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/2023-11-16-_-AfD-Europawahlprogramm-2024-_-web.pdf .Arzheimer, Kai. 2015. “The AfD: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?”

West European Politics 38: 535–56.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230 .———. 2023. “Is the AfD’s Surge in the Polls Real?”

https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/is-the-afds-surge-in-the-polls-real/ .———. 2024. “Both Putin’s Poodle and China’s Tool? The AfD Had a Terrible Week, and More’s to Come.”

https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/both-putins-poodle-and-chinas-tool-the-afd-had-a-terrible-week-and-mores-to-come/ .Arzheimer, Kai, and Carl Berning. 2019. “How the

Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013-2017.”

Electoral Studies 60: online first.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004 .German Bundestag. 2017a. “Dr. Anton Friesen.”

https://www.bundestag.de/webarchiv/abgeordnete/biografien19/F/519566-519566 .———. 2017b. “Waldemar Herdt.”

https://www.bundestag.de/webarchiv/gesetze/biografien19/H/520322-520322 .———. 2021. “Eugen Schmidt.”

https://www.bundestag.de/gesetze/biografien/S/schmidt_eugen-861178 .Deutschlandfunk. 2022. “Weidel sees an ‘economic war against Germany’.”

https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/alice-weidel-afd-ukraine-krieg-100.html .FAZ. 2014. “AfD for division of the country.”

https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/afd-fuer-spaltung-der-ukraine-12888098.html .———. 2018. “Russians paid for private plane for AfD politician.”

https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/russen-bezahlten-privatflugzeug-fuer-afd-politiker-15600740.html .Research Group Elections. nd “Politics II: Long-term development of important trends from the Politbarometer on political topics.” Accessed June 13, 2024.

https://www.forschungsgruppe.de/Umfragen/Politbarometer/Langzeitentwicklung_-_Themen_im_Ueberblick/Politik_II/ .Gatehouse, Gabriel. 2019. “German Far-Right MP ‘Could Be Absolutely Controlled by Russia’.”

BBC Newsnight , April.

German far-right MP ‘could be absolutely controlled by Russia’ .Greene, Toby. 2023. “Natural Allies? Varieties of Attitudes Towards the United States and Russia Within the French and German Radical Right.” Nations and Nationalism .

https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12957 .Gude, Ken. 2017. “Russia’s 5th Column.” Center for American Progress.

https://www.americanprogress.org/article/russias-5th-column/ .Today, ZDF. 2022. “Chrupalla on Lanz about Putin: ‘For me he is not a war criminal.’”

https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/video/politik-lanz-chrupalla-putin-kriegsverbrechen-100.html .Ivaldi, Gilles, and Emilia Zankina. 2023. “Introduction.” In The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe , edited by Gilles Ivaldi and Emilia Zankina, 16–30. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS).

https://doi.org/10.55271/rp0034 .Jaeger, Mona, and Friedrich Schmidt. 2017. “Guesting with friends.”

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , no. 45 (February): 2.Jennerjahn, Miro. 2016. “Saxony as the Origin of the Nationalist-Racist Movement PEGIDA.” In

Strategies of the Extreme Right. Backgrounds – Analyses – Answers , edited by Stephan Braun, Alexander Geisler, and Martin Gerster, 2nd ed., 533–58. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.Joswig, Gareth. 2022. “AfD cancels its travel plans.” TAZ , September.

https://taz.de/AfD-Abgeordnete-in-Russland/!5883129/ .Klinke, Ian. 2018. “Geopolitics and the Political Right: Lessons from Germany.”

International Affairs 94 (3): 495–514.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiy024 .Lachmann, Günther. 2013. “The AfD wants to return to Bismarck’s foreign policy.” Welt , September.

https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article119895035/Die-AfD-will-zurueck-zu-Bismarcks-Aussenpolitik.html .Litschko, Konrad. 2014. “The ‘Friendly Russia’ of the AfD.” TAZ , March.

https://taz.de/Parteitag-in-Erfurt/!5045868/ .Maegerle, Anton. 2009. “The International of Nationalists: Connections of German Right-Wing Extremists – Using the NPD/JN as an Example – to Like-Minded People in Selected Eastern European States.” In Strategies of the Extreme Right: Backgrounds – Analyses – Answers , edited by Stephan Braun, Alexander Geisler, and Martin Gerster, 461–73. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-91708-5_24 .Mai, Marina. 2016. “The AfD’s favorite migrants.” TAZ , April.

https://taz.de/Russlanddeutsche-in-Berlin/!5335943/ .Nefzger, Andreas. 2022. “Cold in the Heart.”

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung , no. 191 (August): 1.Ostermann, Falk, and Bernhard Stahl. 2022. “Theorizing Populist Radical-Right Foreign Policy: Ideology and Party Positioning in France and Germany.” Foreign Policy Analysis 18 (3): 1–22.

https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/orac006 .Patton, David F. 2024. “The Ukraine War as a Driver of Intraparty Conflict: Germany’s Left Party and the AfD.” German Politics online first (0): 1–26.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2024.2326466 .“Plenary Protocol 20/20.” 2022. The German Bundestag.

https://dserver.bundestag.de/btp/20/20020.pdf .Riedel, Katja, Florian Flade, and Sebastian Pittelkow. 2024. “Office of former Krah employee searched.”

Tagesschau , May.

https://www.tagesschau.de/investigativ/ndr-wdr/krah-afd-durchsuchung-eu-100.html .Sablina, Lilia. 2021. “”We Should Stop the Islamization of Europe!”: Islamophobia and Right-Wing Radicalism of the Russian-Speaking Internet Users in Germany.” Nationalities Papers 49(2): 361–74.

https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2019.76 .Schneider, Theo. 2017. “Right-wing Russian Germans Pro AfD.” Endstation Rechts , March.

https://www.endstation-rechts.de/news/rechte-russlanddeutsche-pro-afd .Shein, SA, and EN Ryzhkin. 2024. “Towards a Common Vision? Populist Radical Right Parties’ Positions on the EU Common Foreign and Security Policy Towards Russia.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 32 (1): 291–300.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2023.2235576 .Spiegel, Der. 2020. “AfD politician admits sponsorship from Moscow.”

https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/krim-reise-afd-politiker-gibt-sponsoring-aus-moskau-zu-a-4a6c1b1a-e82d-4268-a658-fb78a3fc4ed8 .———. 2024. “New searches of AfD politician Bystron.”

https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/razzia-in-berlin-neue-durchsuchungen-bei-afd-politiker-bystron-a-a4cb851e-d735-42d6-8301-6f989c60dcfa .Spies, Dennis Christopher, Sabrina Jasmin Mayer, Jonas Elis, and Achim Goerres. 2022. “Why Do Immigrants Support an Anti-Immigrant Party? Russian-Germans and the Alternative for Germany.”

West European Politics online first: 1–25.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2022.2047544 .Sternberg, Jan. 2022. “Old wine in new bottles: AfD makes inflation its new campaign theme.” RND , July.

https://www.rnd.de/politik/neue-kampagne-der-afd-wie-die-partei-das-inflationsthema-fuer-sich-nutzen-will-Y4YWHMHUMRE7JDZ42N7VT7STQI.html .Stöber, Silvia, and Andrea Becker. 2021. “’Election observation on demand’.” Tagesschau , September.

https://www.tagesschau.de/investigativ/kontraste/russland-demokratie-wahlbeobachtung-101.html .Tagesschau. nd “Strategy for the AfD from the Kremlin?” Accessed June 14, 2024.

https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/innenpolitik/kreml-strategiepapier-afd-100.html .Wood, Steve. 2021. “’Understanding’ for Russia in Germany: International Triangle Meets Domestic Politics.”

Cambridge Review of International Affairs 34 (6): 771–94.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1703647 .Zeit Online. 2021. “Alice Weidel travels to Russia with AfD colleagues.”

Notes

- For the “left”, China and the USA come first, followed by “against”, “Russia”, “with”, “opposite”, “Ukraine” and only then “sanctions”. For the other parties, which are considered together here, “Russia” is also most strongly associated with “China” and “USA”. Sanctions only follow in twelfth place. ↩︎

- The analysis is based on version v2.1.0-rc2 of the GermaParl corpus ( https://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10416536 ). In the case of the USA, “America” and “United States” were considered synonyms for counting the country names. A window of five words before and after the word “Russia” was used to determine the collocations. ↩︎

- (Alternative für Deutschland 2017c, 154) . In June 2024, there was still a little-used Facebook page associated with the group, but the website linked there has since been shut down. The website of the “Russian Germans for the AfD NRW” ( https://russlanddeutsche-afd.nrw/ ) has also not been updated since August 2021. ↩︎

- Friesen belonged to the association “Expellees, Repatriates and German Minorities in the AfD”, the “Christians in the AfD” and (as a supporting member) the “Jews in the AfD” (see German Bundestag 2017a) . Herdt was a member of the “Coordination Center of Russian Germans ‘For the German Homeland!’”, holder of a “power of attorney” from the “International Convention of Russian Germans” and a founding member of the “Group for Expellees, Repatriates and German Minorities” of the AfD parliamentary group (see German Bundestag 2017b) . This “convention” was a relatively small organization around the right-wing Russian German activist Heinrich Groth , which became known primarily in connection with the Russian propaganda campaign surrounding the alleged “Lisa case”. The “coordination center” was founded by those around the “convention” to support the AfD. Former NPD officials were also involved (Schneider 2017) . ↩︎

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.