Dealing with any kind of German subnational data teaches one the Zen of German Politics. Germany may have a National Office for Statistics, but of course each federal state has its own Office, with their own definitions, procedures, traditions, websites etc. That alone makes dealing with reasonably fine-grained official data an exquisite pain.

One particularly subtle aspect of this pain is that the very structure of subnational government varies from state to state. Today (2022), about 11,000 municipalities exist in unified Germany. That’s down from roughly 24,000 that existed during the 1950s in the Federal Republic.

2,300 of the present-day municipalities – basically the same number that we had in the late 1970s – are in Rhineland-Palatinate alone, although this state is home to just 5 per cent of the nation’s population. After a series of mergers, Saxony, which has about the same number of inhabitants as Rhineland-Palatinate, retains just over 400 municipalities, down from 1,600 that existed in 1991. Berlin (4.5 per cent of Germany’s population) is a single municipality. In short, the meaning of “municipality” varies wildly, and municipal data (where it exists and is accessible) is usually neither comparable nor otherwise particularly useful.

Thankfully, an intermediate level of government called districts exist in each Land but Berlin and Hamburg. These ~400 districts are either rural (that’s the majority) or urban (basically self-governing towns and cities).

While there is considerable variation across districts (the smallest urban districts are towns with just over 30,000 inhabitants while the whole of Berlin is treated like a district, too), a lot of official data has been harmonised at this level and is available in machine-readable form. Yay! However, while districts tend to be relatively stable, every now and then the states’ desire to meddle become more efficient leads to mergers and other reforms, which can in turn bite your ankles when you try to match survey and macro data.

More specifically, you may find that you have interviewed people in two adjacent districts that partially merged later that year, with some leftover municipalities going to a third district. And because you interviewed in early summer while the border changes went in effect in autumn, a bit of recoding is required for the matching to make sense.

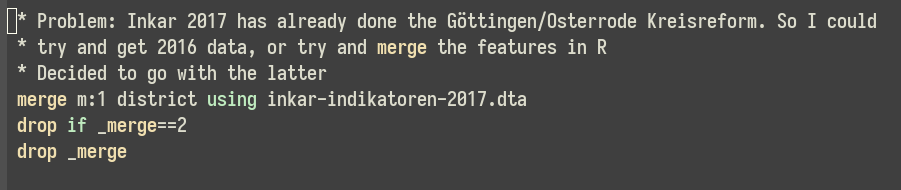

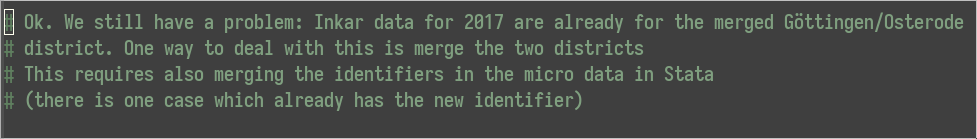

Information on such border changes is difficult to come by and easy to forget, and so I was nearly moved to tears when I saw that past me (of six months aho) – usually a sloppy bastard who heavily discounts the future – had left a note for present me regarding the merger of Göttingen and Osterrode districts, and how he dealt with this particular problem in Stata.

But I was positively shocked to find out that the bugger had left a corresponding message in a second script on the R side of things – because he had already half forgotten what his past me had told him a few hours earlier? Or was it really concern for future me (me)? Either way, future me shouldn’t hope that present me is as conscientious as past me used to be. Because present me is usually the laziest bugger of them all.

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.