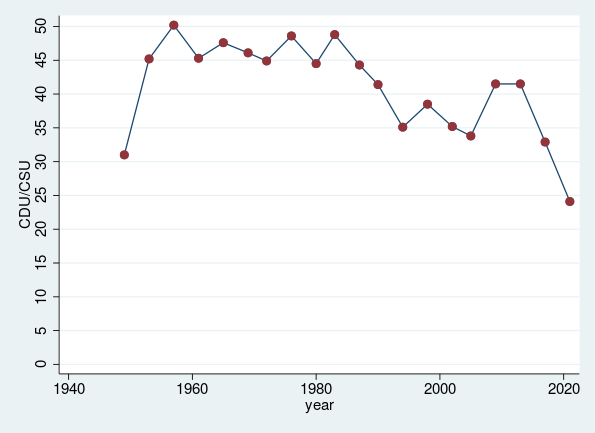

A week ago, Germany’s alliance of Christian Democratic parties posted its worst national election result ever: they lost nine points on their (already pretty disappointing) 2017 result. For what it’s worth, these results are in line with a long-term downward trend that was briefly reversed in the 2005 and 2009 elections.

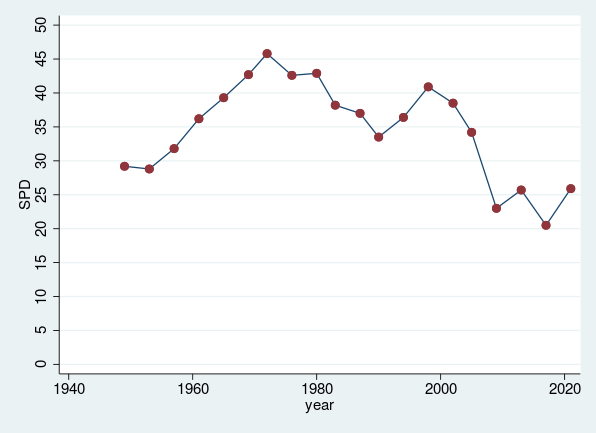

The Social Democrats emerged as the election’s big winner, partly because they improved on their abysmal 2017 result and emerged as the biggest party, but also because for a long time, the polls had suggested that they would fall well below 20 per cent. But from a historical perspective, their result is pretty weak. All this is hardly surprising, because party identification, or at least identification with the former main parties, has been in decline for a long, long time.

Because no-one wants to form a coalition with the AfD, and because the Left is almost as isolated and moreover to weak to be a necessary part of a coalition, that leaves us with three options: the “traffic light” (SPD, Greens, FDP) and “Jamaica” (CDU, Greens, FDP) coalitions, and a reversed “Grand Coalition” (SPD/CDU). The latter has some limited use as leverage for the bigger parties and insurance against minority government and fresh elections, but is deeply unpopular with voters and also the respective parties.

Jamaica looked like a non-starter on election night and has become even less likely: the CDU (and to a much lesser degree the CSU) is in disarray, fighting over its leadership and future course. This would make them a very awkward partner for the smaller parties. Moreover, in the days after the election, the discourse has focused on the SPD winning and the CDU losing the election. Laschet, the CDU/CSU’s candidate for the chancellorship, always had terrible ratings and is widely seen as one important factor contributing to the Christian Democrats’ disaster. Installing him in the chancellery would hardly chime with the Greens’ and FDP’s message of reform and modernisation.

The most likely result of this is the “traffic light”, which would be Germany’s most secular coalition since (probably) the 1970s. Why is this? While this may change in the future, Germany is currently a typical “religious world” country, where conflict over the role of religion in public life is reflected in the structure of the party system. The name of Germany’s dominant party gives a strong hint: the religious/secular cleavage is embodied in the CDU/CSU. And this is not just tradition and the proverbial “C” in their name: At least in the 2009-13 Bundestag, MPs for the Christian Democrats had a surprisingly large number of affiliations with religious groups and institutions. However, the Greens scored almost as high on this measure.

| Party | mean number of affiliations |

|---|---|

| CDU | 0.6 |

| CSU | 0.3 |

| SPD | 0.3 |

| FDP | 0.2 |

| Greens | 0.5 |

| Left | 0.1 |

| Total | 0.4 |

An analysis of the crucial free vote that legalised Preimplantation Genetic Testing in Germany shows that even after controlling for these remarkable differences, MPs for the SPD and particularly the FDP were much more likely to support legalisation. This is in line with secular traditions in both parties. The FDP in particular has consistently voted for more liberal (again, the hint is in the name) bioethical rules.

On the other hand, the voting behaviour of Green MPs did not differ significantly from that of their CDU counterparts.1 Again, this is not terribly surprising: while the Greens are by and large a left-libertarian outfit, Christian movements for peace and the protection of the environment are part of their heritage. Winfried Kretschmann, their only Minister President, is a devout Catholic who runs a coalition with the CDU and likes to stress that they operate on a base of common values. The long-standing leader of their parliamentary party, Katrin Göring-Eckardt, studied theology (although she never graduated) and was the top lay person involved in the leadership of Germany’s Protestant Church as president of its synod from 2009-13. She also is in favour of compulsory religious education in schools and supports the (remaining) exemptions from workers’ rights for church-run hospitals, care-homes and kindergartens.

Of course, the numbers above are from 2011. Many new MPs for the Greens are very young, and I have no idea how important that Christian strain is for the new parliamentary party. Either way, with the Christian Democrats out of government, the new government will by definition be more secular than the last four, and bringing in the FDP might make them more secular than the Schröder governments. If and how this will affect actual policies is, of course, a different question that is way too nuanced for a blog post.

Footnotes:

Conversely, the CSU MPs displayed more restrictive preferences than anyone else.

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Likes

Reposts

Mentions