How it started: far right governments as an exception

A decade or two ago, far right governments were a rarity in Europe. Of course, there were the Berlusconi governments of the 1990s and early 2000s that included the radical right Lega (then still the Lega Nord) and the post-fascist Alleanza Nazionale, i.e. the rebranded MSI. But outside Italy, that was mostly something that excited the anoraks. Conversely, when the Austrian ÖVP formed a coalition with Jörg Haider’s FPÖ, the other EU governments scaled down their bilateral contacts with the administration and even sent a group of Three Wise Men to check the pulse of Austrian democracy, although within a few months, everything went back to normal.

12 year after these events, my friend and colleague Sarah de Lange published an excellent article in which she argues that a) Europe has shifted to the right and b) mainstream and radical right parties have moved closer together so that c) the radical right becomes an attractive partner for the mainstream right. Sarah also pointed out that these “New Alliances” between the centre and the radical right are risky for the latter, as there is a good chance that they cock up and/or disappoint their supporters once they are in government. You can hear her talk about her article in an excellent podcast episode.

Sarah’s article was for quite some time my go-to reference for the question of why and how radical, authoritarian, ultranationalist parties end up in government. Yet, another 12 years later, when I was updating the reading list for my dear old seminar on radical right-wing populism in Europe, I felt the need to replace it with something newer.

How it’s going: the normalisation of far right government

And that is because governments that include at least one nativist party are even less unusual today: The reborn and renamed Alleanza has governed Italy for nearly two years, with the Lega and the remains of Berlusconi’s party as junior partners. Geert Wilders did not become Prime Minister, but his one-person party nonetheless leads the new Dutch government. Then there are Finland and Norway, let alone Hungary and Poland, and, in what could have been a very fitting end to our semester, Marine Le Pen came closer than ever to the levers of government. Far right ideology has become commonplace, and the calculus for the mainstream right may have changed even further.

So I replaced Sarah’s article with this one by Nicolas Bichay (open access), which also has a lot going for it. Its main thesis is that although there are costs and considerable risks, mainstream parties (mostly on the right) co-opt radical right parties into coalitions if they perceive them as an “electoral threat”. The idea of threat remains a bit vague and does not fit perfectly with the other theoretical premises (mostly standard coalition formation theory and Bonnie Meguid’s classic about mainstream parties and niche party success).

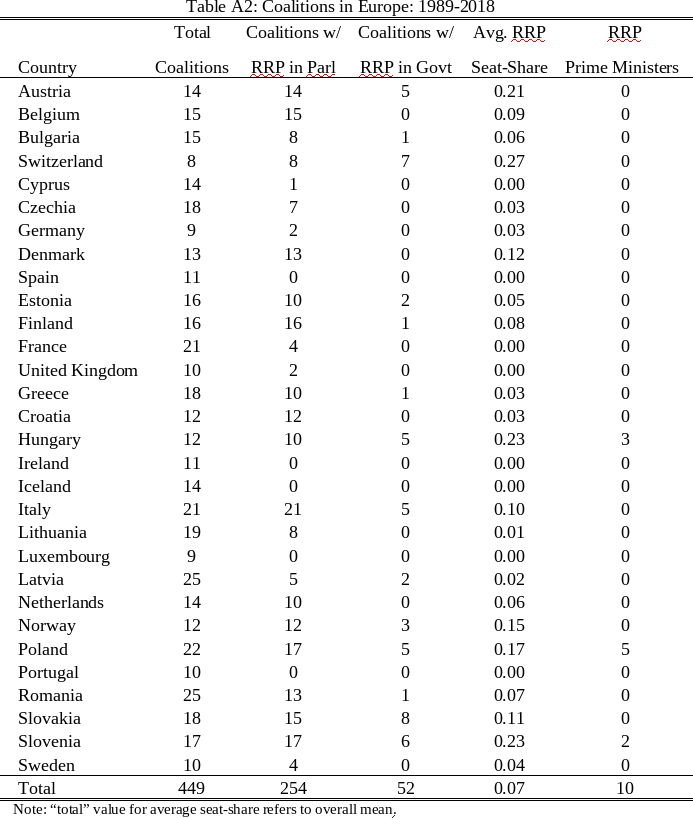

But funnily enough, the actual operationalisation is quite convincing, and so is the statistical model. The main finding is that four indicators for threat or rather for perceptions of threat — long-term economic declining, asylum seeker inflows, negative views on immigration, and radical right success in neighbouring countries — all make the inclusion of radical right wing parties more likely.

Bichay has also written a companion article that looks at the effect that radical right junior coalition partners have on the quality of democracy in Europe (governments led by the far right are thankfully still exceedingly rare). While I wonder how a model that looks so saturated with controls can be identified, the results suggest that even as a junior partner who controls only some departments, the radical right erodes general civic liberties and specific minority protections. The status of “out-groups” like Muslims, (certain) women, and sexual minorities declines.

Of course, there is a lot more research on the consequences of radical right success both inside and outside government (another reading list). But Bichay’s second article is recent, focused, and concise, and so I assigned that one, too.

The bottom line is, of course, somewhat depressing. While far right Prime Ministers, who tend to change the institutions to remove checks and balances, are still relatively rare, the once-taboo inclusion of radical right parties in democratic governments is now quite common (Bichay identifies 42 such governments that existed between 1989 and 2018). The older literature probably understates their impact and overstates the “disenchantment” effect.

The cordon sanitaire has been broken in many countries. And beyond policies that we like or more often don’t like, this has real, tangible consequences for the quality of democracy.

- Bichay, Nicolas. “Populist Radical-Right Junior Coalition Partners and Liberal Democracy in Europe.” Party Politics (2022): online first. doi:10.1177/13540688221144698

- Bichay, Nicolas. “Come Together: Far-Right Parties and Mainstream Coalitions.” Government and Opposition (2023): 1–22. doi:10.1017/gov.2023.5

- de Lange, Sarah L. “New Alliances. Why Mainstream Parties Govern with Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties.” Political Studies 60.4 (2012): 899–918. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00947.x

- Meguid, Bonnie M. “Competition Between Unequals: The Role of Mainstream Party Strategy in Niche Party Success.” American Political Science Review 99.3 (2005): 347–359. doi:10.1017/S0003055405051701

picture credit: Jörg Haider 04-09-2008″ by sugarmeloncom is licensed under CC BY 2.0.