What’s up with AfD support?

Last winter, Alternative for Germany regularly polled above the symbolic 20% threshold. Panic ensued, and politicians of nearly all stripes reacted — rather predictably — by talking tough on immigration, thereby helping to keep the one issue that the party really owns at the very top of the agenda. The party looked unstoppable, and once more, people on the very right of the CDU even pondered the possibilities of coming to some arrangement with the AfD.

Then, following the (well orchestrated) revelations about the AfD’s connections to the Identitarian Movement and the plans for mass deportations, their polling numbers began to sag a bit in the face of some serious counter-mobilisation. The founding of a new party (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht) that is economically on the left but tries to win over AfD supporters with anti-woke policies also did not help. Nor did the scandals involving the AfD’s connections with China and Russia, or the party leadership’s hapless attempts at damage limitation.

Consequentially, the pendulum in newsrooms has swung in the other direction, and journalists have begun to write off the AfD. Of course, this is nonsense. Here is the real story, brought to you by actual science.

Down, but far from out: polling support for the AfD in perspective

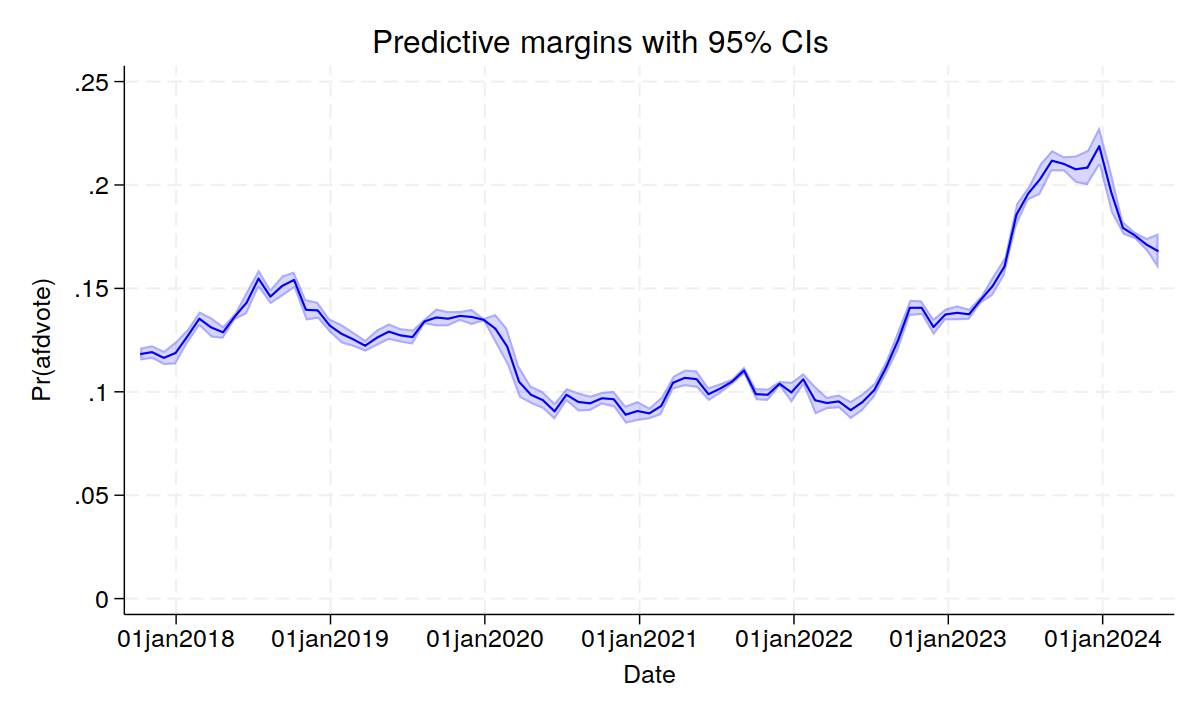

Aggregating over hundreds of surveys that were conducted since 2017 produces a smooth and hopefully precise estimate of their support. From the graph, it is easy to see that AfD support hovered between 12 and 15 per cent for their first two years in parliament, then dropped to roughly 10 per cent once Covid-19 became the dominant issue in Germany.

Although the AfD, after some initial confusion, aligned itself with “lateral thinkers”, anti-vaxxers and Covid-deniers (and attracted a lot of attention this way), it did not have a good pandemic and remained stuck just above/below the 10 per cent mark. Presumably, many members of this new constituency were ideologically close to the AfD, while those AfD supporters who actually favoured stricter measures defected to other parties.

Against this backdrop, it is not surprising that the AfD suffered a net loss of two percentage points in the 2021 election and drew just 10.4 per cent of the vote (it’s nice to see how well the pooled survey data match this result). It’s reasonable to assume that these 10 per cent represent the hard core of the AfD’s electorate, and it was also tempting to assume that AfD support would remain mostly confined to this group as the public learned more and more about extremist tendencies within the party and its connections with extremist actors outside the party proper.

However, this is not what happened. When imports of Russian natural gas dwindled and then ceased while inflation rose in the second half of 2022, the AfD quite openly declared that they would not let a good crisis go to waste. They already were the party most firmly opposed to any sort of decarbonisation and ecological transformation of the economy. Now they became the party of those who are (at least) sceptical about Germany’s support for Ukraine.

But the effect of the winter of discontent seemed limited at first: even during the coldest period of the year, AfD support remained (just) below its mid-2018 peak. This only changed (and then quite rapidly) during the summer of 2023.

2023/2024: the rise and moderate fall of AfD support

By and large, this has not caused huge frictions. Unlike 2015/16, there were few makeshift shelters in school gymnasiums or scenes of chaos at train stations. Moreover, the demographics of the new arrivals — white, often female, Christian or at least not Muslim — created less of a media frenzy and much lower levels of public anxiety than the so-called refugee crisis of 2015/16.

There was, however, a very public conflict between municipalities/districts (who provide most social and other services) and the federal government about the costs of hosting the Ukrainian refugees that made headlines over several months. Why the federal government let this escalate and kept this alive for so long is beyond me. Also, the Christian Democrats (and even the liberal democrats, nominally part of the government) tried their hand at pinching the AfD’s rhetoric, style, and issues, because that has worked so well in the past.

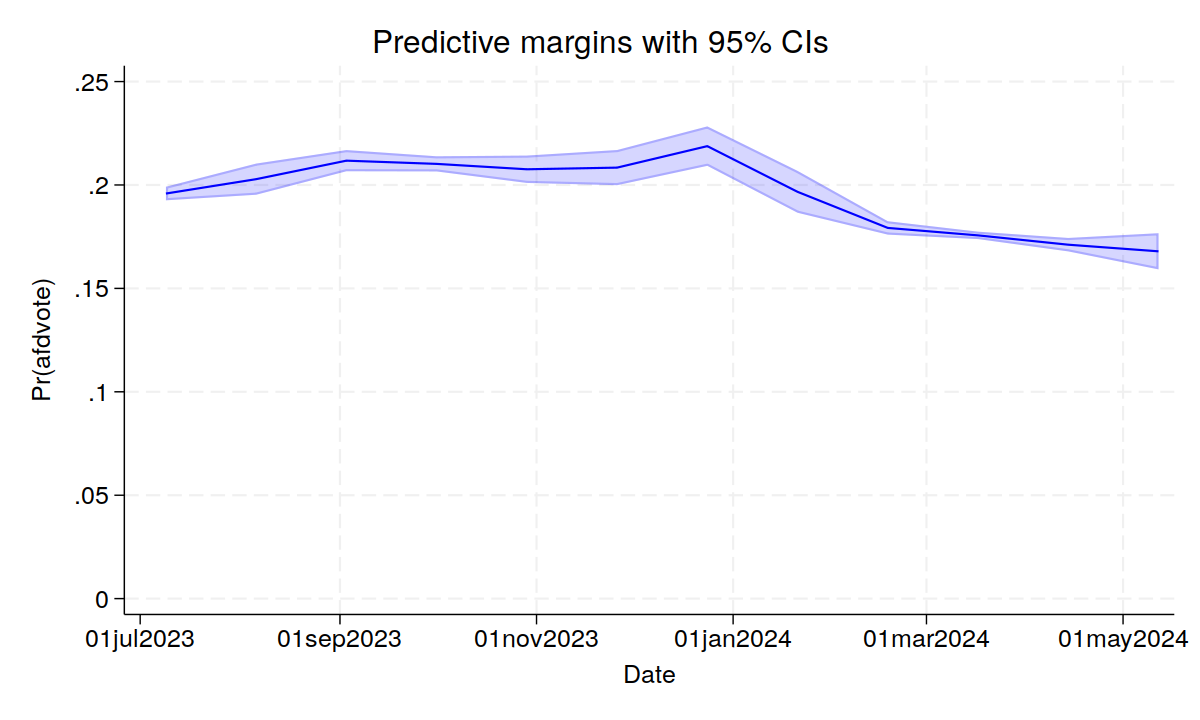

As a result, “foreigners/immigration/refugees” became the most important issue for 50 per cent of voters during the summer and early fall of 2023 (up from less than 10 per cent earlier that year and now down to about 30 per cent). And I’m not going out on a limb when I say that this helped the AfD during a period when worries about Russia/Ukraine had declined.

In the graph, it is easy to see that the AfD support passed the 20 per cent line at some point in September 2023 and basically remained above that threshold for the remainder of the year, with a nice season-of-goodwill-and-appreciation bump around Christmas. January (the month when the deportation story broke) brought a pronounced decline (the fact that the line bends down during the last week of December is arguably an artefact of the aggregation). Like November and December, it also brought a lot of polling noise that makes for wider confidence intervals.

By February 2024, AfD support was below 20 per cent for the first time since June, and by March, it had stabilised at 17 per cent.

And these are the underreported (or underhyped) parts of the story:

First, the confidence interval is currently remarkable narrow. All the polls more or less agree that this is where the party is, give or take a single point. More specifically, all the reports about Chinese spies and Russian money that came out in April have not moved the needle one bit.

Second, support for the party has come down 5 percentage points in the space of four months, which is kind of big. But all the scandals, all the news about their extremist tendencies (which include a former AfD MP that is currently standing trial on charges of terrorism and high treason) notwithstanding, the AfD is still polling 6 or 7 points above their last national election result.

Unless something (even more) dramatic happens, this would give them 16 or 17 of Germany’s 96 seats in the EP, up from 11 in 2019. As we in the trade are fond of saying: What the actual fuck?

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.