Introduction

Since the early 1990s, the radical right has become a relevant party family in most West European polities including many of Germany’s neighbours such as Austria, Belgium (Flanders), Denmark, France, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. For decades, Germany remained a negative outlier. Parties like the DVU, the NPD, and the Republicans had some success at the local and regional level but never managed to escape from the shadow of “Grandpa’s Fascism”. This only changed with the rise, transformation and electoral breakthrough of “Alternative for Germany”, or AfD for short, a new party that was founded in 2013. Within a span of just over three years, the AfD established itself as the predominant political actor on the far right.

- Arzheimer, Kai. “Im Osten nichts Neues? Die elektorale Unterstützung von AfD und Linkspartei in den alten und neuen Bundesländern bei der Bundestagswahl 2021.” Wahlen und Wähler – Analysen zur Bundestagwahl 2021. Eds. Schoen, Harald and Bernhard Weßels. Wiesbaden: Springer, 2024. 139-178. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-42694-1_6

[BibTeX] [Download PDF] [HTML]@InCollection{arzheimer-2023c, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {Im Osten nichts Neues? Die elektorale Unterstützung von AfD und Linkspartei in den alten und neuen Bundesländern bei der Bundestagswahl 2021}, booktitle = {Wahlen und Wähler - Analysen zur Bundestagwahl 2021}, publisher = {Springer}, year = 2024, editor = {Schoen, Harald and Weßels, Bernhard}, address = {Wiesbaden}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/bundestagswahl-2021-ostdeutschland-linkspartei-afd.pdf}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/bundestagswahl-2021-ostdeutschland-linkspartei-afd/}, dateadded = {14-11-2022}, doi = {10.1007/978-3-658-42694-1_6}, pages = {139-178} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “Identification with an anti-system party undermines diffuse political support: The case of Alternative for Germany and trust in the Federal Constitutional Court.” Party Politics 31.3 (2024): 397-409. doi:10.1177/13540688241237493

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [HTML]The rise of the far right is increasingly raising the question of whether partisanship can have negative consequences for democracy. While issues such as partisan bias and affective polarization have been extensively researched, little is known about the relationship between identification with anti-system parties and diffuse system support. I address this gap by introducing a novel indicator and utilising the GESIS panel dataset, which tracks the rise of a new party, “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) from 2013, when the party was founded, to 2017, when the AfD, now transformed into a right-wing populist and anti-system party, entered the federal parliament for the first time. Employing a panel fixed effects design, I demonstrate that identification with “Alternative for Germany” reduces trust in the Federal Constitutional Court by a considerable margin. These findings are robust across various alternative specifications, suggesting that the effects of anti-system party identification should not be dismissed.

@Article{arzheimer-2024, author = {Kai Arzheimer}, title = {Identification with an anti-system party undermines diffuse political support: The case of Alternative for Germany and trust in the Federal Constitutional Court}, journal = {Party Politics}, year = 2024, volume = 31, number = 3, pages = {397-409}, keywords = {EuroReX, AfD}, abstract = {The rise of the far right is increasingly raising the question of whether partisanship can have negative consequences for democracy. While issues such as partisan bias and affective polarization have been extensively researched, little is known about the relationship between identification with anti-system parties and diffuse system support. I address this gap by introducing a novel indicator and utilising the GESIS panel dataset, which tracks the rise of a new party, "Alternative for Germany" (AfD) from 2013, when the party was founded, to 2017, when the AfD, now transformed into a right-wing populist and anti-system party, entered the federal parliament for the first time. Employing a panel fixed effects design, I demonstrate that identification with "Alternative for Germany" reduces trust in the Federal Constitutional Court by a considerable margin. These findings are robust across various alternative specifications, suggesting that the effects of anti-system party identification should not be dismissed.}, doi = {10.1177/13540688241237493}, pdf = {https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/13540688241237493}, html = {https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/13540688241237493} } - Arzheimer, Kai, Theresa Bernemann, and Timo Sprang. “Oppression of Catholics in Prussia Does Not Explain Spatial Differences in Support for the Radical Right in Germany. A Critique of Haffert (2022).” Electoral Studies 89 (2024): 102789. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2024.102789

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [HTML]A growing literature links contemporary far-right mobilization to the “legacies” of events in the distant past, but often, the effects are small, and their estimates appear to rely on problematic assumptions. We re-analyse Haffert’s (2022) study, a key example of this strand of research. Haffert claims that historical political oppression of Catholics in Prussia moderates support for the radical right AfD party among Catholics in contemporary Germany. While the argument itself has intellectual merit, we identify some severe limitations in the empirical strategy. Retesting the study’s cross-level interaction hypothesis using more suitable multi-level data and a more appropriate statistical model, we find a modest overall difference in AfD support between formerly Prussian and non-Prussian territories. However, this difference is unrelated to individual Catholic religion or to the contextual presence of Catholics. This contradicts the oppression hypothesis. Our study thus provides another counterpoint to the claim that historical events have strong and long-lasting effects on contemporary support for the radical right. We conclude that simpler explanations for variations in radical right support should be exhausted before resorting to history.

@Article{arzheimer-bernemann-sprang-2024, author = {Arzheimer, Kai and Bernemann, Theresa and Sprang, Timo}, title = {Oppression of Catholics in Prussia Does Not Explain Spatial Differences in Support for the Radical Right in Germany. A Critique of Haffert (2022)}, journal = {Electoral Studies}, year = 2024, volume = 89, pages = 102789, abstract = {A growing literature links contemporary far-right mobilization to the "legacies" of events in the distant past, but often, the effects are small, and their estimates appear to rely on problematic assumptions. We re-analyse Haffert's (2022) study, a key example of this strand of research. Haffert claims that historical political oppression of Catholics in Prussia moderates support for the radical right AfD party among Catholics in contemporary Germany. While the argument itself has intellectual merit, we identify some severe limitations in the empirical strategy. Retesting the study's cross-level interaction hypothesis using more suitable multi-level data and a more appropriate statistical model, we find a modest overall difference in AfD support between formerly Prussian and non-Prussian territories. However, this difference is unrelated to individual Catholic religion or to the contextual presence of Catholics. This contradicts the oppression hypothesis. Our study thus provides another counterpoint to the claim that historical events have strong and long-lasting effects on contemporary support for the radical right. We conclude that simpler explanations for variations in radical right support should be exhausted before resorting to history.}, html = {https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261379424000477}, pdf = {https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0261379424000477/pdfft?md5=8b0c75faf974eb845135c7c1e0f41c14&pid=1-s2.0-S0261379424000477-main.pdf}, doi = {10.1016/j.electstud.2024.102789} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “Die AfD und Russland.” Jahrbuch Extremismus und Demokratie. Eds. Backes, Uwe, Alexander Gallus, Eckhard Jesse, and Tom Thieme. Vol. 36. Nomos, 2024. 207-220.

[BibTeX] [HTML]@InCollection{arzheimer-2024b, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {Die AfD und Russland}, booktitle = {Jahrbuch Extremismus und Demokratie}, pages = {207-220}, publisher = {Nomos}, year = 2024, editor = {Uwe Backes and Alexander Gallus and Eckhard Jesse and Tom Thieme}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-russland-verbindung/}, volume = 36, dateadded = {25-06-2024} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “The Electoral Breakthrough of the AfD and the East-West Divide In German Politics.” Contemporary Germany and the Fourth Wave of Far-Right Politics: From the Streets to Parliament. Ed. Weisskircher, Manès. London: Routledge, 2023. 140-158.

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [HTML]The radical right became a relevant party family in most west European polities in the 1990s and early 2000s, but Germany was a negative outlier up until very recently. Right-wing mobilisation success remained confinded to the local and regional level, as previous far-right parties never managed to escape from the shadow of “Grandpa’s Fascism”. This only changed with the rise, electoral breakthrough, and transformation of “Alternative for Germany” (AfD), which quickly became the dominant far-right actor. Germany’s “new” eastern states were crucial for the AfD’s ascendancy. In the east, the AfD began to experiment with nativist messages as early as 2014. Their electoral breakthroughs in the state elections of this year helped sustain the party through the wilderness year of 2015 and provided personel, ressources, and a template for the AfD’s transformation. Since its inception, support for the AfD in the east has been at least twice as high as in the west. This can be fully explained by substantively higher levels of nativist attitudes in the eastern population. As all alleged causes of this nativism are structural, the eastern states seem set to remain a stronghold for the far right in the medium- to long-term.

@InCollection{arzheimer-2021, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {The Electoral Breakthrough of the AfD and the East-West Divide In German Politics}, booktitle = {Contemporary Germany and the Fourth Wave of Far-Right Politics: From the Streets to Parliament}, publisher = {Routledge}, editor = {Weisskircher, Manès}, year = 2023, pages = {140-158}, address = {London}, abstract = {The radical right became a relevant party family in most west European polities in the 1990s and early 2000s, but Germany was a negative outlier up until very recently. Right-wing mobilisation success remained confinded to the local and regional level, as previous far-right parties never managed to escape from the shadow of “Grandpa’s Fascism”. This only changed with the rise, electoral breakthrough, and transformation of “Alternative for Germany” (AfD), which quickly became the dominant far-right actor. Germany’s “new” eastern states were crucial for the AfD’s ascendancy. In the east, the AfD began to experiment with nativist messages as early as 2014. Their electoral breakthroughs in the state elections of this year helped sustain the party through the wilderness year of 2015 and provided personel, ressources, and a template for the AfD’s transformation. Since its inception, support for the AfD in the east has been at least twice as high as in the west. This can be fully explained by substantively higher levels of nativist attitudes in the eastern population. As all alleged causes of this nativism are structural, the eastern states seem set to remain a stronghold for the far right in the medium- to long-term.}, keywords = {eurorex,afd}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/paper/afd-east-west-cleavage-breakthrough/}, dateadded = {12-04-2021} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “To Russia with love? German populist actors’ positions vis-a-vis the Kremlin.” The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe. Eds. Ivaldi, Gilles and Emilia Zankina. Brussels: European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS), 2023. 156-167. doi:10.55271/rp0020

[BibTeX] [Abstract]Russia’s fresh attack on Ukraine and its many international and national repercussions have helped to revive the fortunes of Germany’s main radical right-wing populist party ‘Alternative for Germany’ (AfD). Worries about traditional industries, energy prices, Germany’s involvement in the war and hundreds of thousands of refugees arriving in Germany seem to have contributed to a modest rise in the polls after a long period of stagnation. However, the situation is more complicated for the AfD than it would appear at first glance. While many party leaders and the rank-and-file have long held sympathies for Putin and more generally for Russia, support for Ukraine is still strong amongst the German public, even if there is some disagreement about the right means and the acceptable costs. At least some AfD voters are appalled by the levels of Russian violence against civilians, and the party’s electorate is divided as to the right course of action. To complicate matters, like on many other issues, there is a gap in opinion between Germany’s formerly communist federal states in the East and the western half of the country. As a result, the AfD leadership needs to tread carefully or risk alienating party members and voters in the more populous western states. Beyond the AfD, the current and future consequences of the war have galvanised the larger far-right movement, particularly in the East. Moreover, they have led to further tensions in the left-wing populist “Linke” (left) party, which is traditionally pacifist and highly sceptical of NATO. The majority of the party tries to square commitment to these principles with solidarity with the victims of Russian aggression. A small but very visible faction, however, shows at least a degree of support for Russia and blames NATO and the US for the war.

@InCollection{arzheimer-2023e, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {To Russia with love? German populist actors' positions vis-a-vis the Kremlin}, booktitle = {The Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on Right-Wing Populism in Europe}, publisher = {European Center for Populism Studies (ECPS)}, year = 2023, editor = {Ivaldi, Gilles and Zankina, Emilia}, pages = {156-167}, address = {Brussels}, abstract = {Russia's fresh attack on Ukraine and its many international and national repercussions have helped to revive the fortunes of Germany's main radical right-wing populist party 'Alternative for Germany' (AfD). Worries about traditional industries, energy prices, Germany's involvement in the war and hundreds of thousands of refugees arriving in Germany seem to have contributed to a modest rise in the polls after a long period of stagnation. However, the situation is more complicated for the AfD than it would appear at first glance. While many party leaders and the rank-and-file have long held sympathies for Putin and more generally for Russia, support for Ukraine is still strong amongst the German public, even if there is some disagreement about the right means and the acceptable costs. At least some AfD voters are appalled by the levels of Russian violence against civilians, and the party's electorate is divided as to the right course of action. To complicate matters, like on many other issues, there is a gap in opinion between Germany's formerly communist federal states in the East and the western half of the country. As a result, the AfD leadership needs to tread carefully or risk alienating party members and voters in the more populous western states. Beyond the AfD, the current and future consequences of the war have galvanised the larger far-right movement, particularly in the East. Moreover, they have led to further tensions in the left-wing populist "Linke" (left) party, which is traditionally pacifist and highly sceptical of NATO. The majority of the party tries to square commitment to these principles with solidarity with the victims of Russian aggression. A small but very visible faction, however, shows at least a degree of support for Russia and blames NATO and the US for the war.}, doi = {10.55271/rp0020} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “Regionalvertretungswechsel von links nach rechts? Die Wahl von Alternative für Deutschland und Linkspartei in Ost-West-Perspektive.” Wahlen und Wähler – Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagwahl 2017. Eds. Schoen, Harald and Bernhard Wessels. Wiesbaden: Springer, 2021. 61-80. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-33582-3_4

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML] [DATA]Bei der Bundestagswahl 2017 zeigten sich wiedereinmal dramatische Ost-West-Unterschiede. Diese gingen vor allem auf den überdurchschnittlichen Erfolg von AfD und LINKE in den neuen Ländenr zurück. Die AfD ist vor allem in Thüringen und Sachsen besonders stark , die LINKE in Berlin, aber auch in den Stadtstaaten Bremen und Hamburg sowie in einigen westdeutschen Großstädten. Die Wahlentscheidung zugunsten beider Parteien wird sehr stark von Einstellungen zum Sozialstaat (im Falle der Linkspartei) sowie zur Zuwanderung (im Falle der AfD) bestimmt. Beide Parteien profitieren überdies von einem Gefühl der Unzufriedenheit mit dem Funktionieren der Demokratie. Sobald für diese Faktoren kontrolliert wird, zeigt sich, dass die AfD keinen davon unabhängigen “Ost-Bonus” genießt. Zugleich deuten die Modellschätzungen auf substantielle Einflüsse auf der Wahlkreisebene hin. Im Falle der Linkspartei bleibt dagegen ein substantieller Effekt des Befragungsgebietes erhalten, selbst wenn für die Einstellungen kontrolliert wird. Signifikante Differenzen zwischen den Wahlkreisen gibt es hier nicht.

@InCollection{arzheimer-2019, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {Regionalvertretungswechsel von links nach rechts? Die Wahl von Alternative für Deutschland und Linkspartei in Ost-West-Perspektive}, booktitle = {Wahlen und Wähler - Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagwahl 2017}, publisher = {Springer}, year = 2021, data = {https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/Q2M1AS}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-linkspartei-ostdeutschland/}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-linkspartei-ostdeutschland.pdf}, doi = {10.1007/978-3-658-33582-3_4}, editor = {Schoen, Harald and Wessels, Bernhard}, pages = {61-80}, abstract = {Bei der Bundestagswahl 2017 zeigten sich wiedereinmal dramatische Ost-West-Unterschiede. Diese gingen vor allem auf den überdurchschnittlichen Erfolg von AfD und LINKE in den neuen Ländenr zurück. Die AfD ist vor allem in Thüringen und Sachsen besonders stark , die LINKE in Berlin, aber auch in den Stadtstaaten Bremen und Hamburg sowie in einigen westdeutschen Großstädten. Die Wahlentscheidung zugunsten beider Parteien wird sehr stark von Einstellungen zum Sozialstaat (im Falle der Linkspartei) sowie zur Zuwanderung (im Falle der AfD) bestimmt. Beide Parteien profitieren überdies von einem Gefühl der Unzufriedenheit mit dem Funktionieren der Demokratie. Sobald für diese Faktoren kontrolliert wird, zeigt sich, dass die AfD keinen davon unabhängigen "Ost-Bonus" genießt. Zugleich deuten die Modellschätzungen auf substantielle Einflüsse auf der Wahlkreisebene hin. Im Falle der Linkspartei bleibt dagegen ein substantieller Effekt des Befragungsgebietes erhalten, selbst wenn für die Einstellungen kontrolliert wird. Signifikante Differenzen zwischen den Wahlkreisen gibt es hier nicht.}, address = {Wiesbaden}, dateadded = {01-04-2019} } - Arzheimer, Kai and Carl Berning. “How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013-2017.” Electoral Studies 60 (2019): online first. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML]Until 2017, Germany was an exception to the success of radical right parties in postwar Europe. We provide new evidence for the transformation of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) to a radical right party drawing upon social media data. Further, we demonstrate that the AfD’s electorate now matches the radical right template of other countries and that its trajectory mirrors the ideological shift of the party. Using data from the 2013 to 2017 series of German Longitudinal Elections Study (GLES) tracking polls, we employ multilevel modeling to test our argument on support for the AfD. We find the AfD’s support now resembles the image of European radical right voters. Specifically, general right-wing views and negative attitudes towards immigration have become the main motivation to vote for the AfD. This, together with the increased salience of immigration and the AfD’s new ideological profile, explains the party’s rise.

@Article{arzheimer-berning-2019, author = {Arzheimer, Kai and Berning, Carl}, title = {How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013-2017}, journal = {Electoral Studies}, year = 2019, doi = {10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004}, volume = {60}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/alternative-for-germany-voters}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/alternative-for-germany-party-voters-transformation.pdf}, pages = {online first}, abstract = {Until 2017, Germany was an exception to the success of radical right parties in postwar Europe. We provide new evidence for the transformation of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) to a radical right party drawing upon social media data. Further, we demonstrate that the AfD's electorate now matches the radical right template of other countries and that its trajectory mirrors the ideological shift of the party. Using data from the 2013 to 2017 series of German Longitudinal Elections Study (GLES) tracking polls, we employ multilevel modeling to test our argument on support for the AfD. We find the AfD's support now resembles the image of European radical right voters. Specifically, general right-wing views and negative attitudes towards immigration have become the main motivation to vote for the AfD. This, together with the increased salience of immigration and the AfD's new ideological profile, explains the party's rise.}, dateadded = {01-04-2019} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “‘Don’t mention the war!’ How populist right-wing radicalism became (almost) normal in Germany.” Journal of Common Market Studies 57.S1 (2019): 90-102. doi:10.1111/jcms.12920

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML]After decades of false dawns, the “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) is the first radical right-wing populist party to establish a national presence in Germany. Their rise was possible because they started out as soft-eurosceptic and radicalised only gradually. The presence of the AfD had relatively little impact on public discourses but has thoroughly affected the way German parliaments operate: so far, the cordon sanitaire around the party holds. However, the AfD has considerable blackmailing potential, especially in the eastern states. In the medium run, this will make German politics even more inflexible and inward looking than it already is.

@Article{arzheimer-2019c, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {'Don't mention the war!' How populist right-wing radicalism became (almost) normal in Germany}, journal = {Journal of Common Market Studies}, year = 2019, abstract = {After decades of false dawns, the "Alternative for Germany" (AfD) is the first radical right-wing populist party to establish a national presence in Germany. Their rise was possible because they started out as soft-eurosceptic and radicalised only gradually. The presence of the AfD had relatively little impact on public discourses but has thoroughly affected the way German parliaments operate: so far, the cordon sanitaire around the party holds. However, the AfD has considerable blackmailing potential, especially in the eastern states. In the medium run, this will make German politics even more inflexible and inward looking than it already is.}, volume = {57}, pages = {90-102}, number = {S1}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/right-wing-populism-germany-normalisation}, dateadded = {27-05-2019}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-normalisation-right-wing-populism-germany.pdf}, doi = {10.1111/jcms.12920}, keywords = {EuroReX, AfD} } - Arzheimer, Kai. “The AfD: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?.” West European Politics 38 (2015): 535–556. doi:10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [Download PDF] [HTML] [DATA]Within less than two years of being founded by disgruntled members of the governing CDU, the newly-formed Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has already performed extraordinary well in the 2013 General election, the 2014 EP election, and a string of state elections. Highly unusually by German standards, it campaigned for an end to all efforts to save the Euro and argued for a re-configuration of Germany’s foreign policy. This seems to chime with the recent surge in far right voting in Western Europe, and the AfD was subsequently described as right-wing populist and europhobe. On the basis of the party’s manifesto and of hundreds of statements the party has posted on the internet, this article demonstrates that the AfD does indeed occupy a position at the far-right of the German party system, but it is currently neither populist nor does it belong to the family of Radical Right parties. Moreover, its stance on European Integration is more nuanced than expected and should best be classified as soft eurosceptic.

@Article{arzheimer-2015, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {The AfD: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?}, journal = {West European Politics}, year = 2015, volume = 38, pages = {535--556}, doi = {10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230}, keywords = {gp-e, cp, eurorex}, abstract = {Within less than two years of being founded by disgruntled members of the governing CDU, the newly-formed Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has already performed extraordinary well in the 2013 General election, the 2014 EP election, and a string of state elections. Highly unusually by German standards, it campaigned for an end to all efforts to save the Euro and argued for a re-configuration of Germany's foreign policy. This seems to chime with the recent surge in far right voting in Western Europe, and the AfD was subsequently described as right-wing populist and europhobe. On the basis of the party's manifesto and of hundreds of statements the party has posted on the internet, this article demonstrates that the AfD does indeed occupy a position at the far-right of the German party system, but it is currently neither populist nor does it belong to the family of Radical Right parties. Moreover, its stance on European Integration is more nuanced than expected and should best be classified as soft eurosceptic. }, data = {https://hdl.handle.net/10.7910/DVN/28755}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-right-wing-populist-eurosceptic-germany}, url = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/afd-right-wing-populist-eurosceptic-germany.pdf} }

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Many observers have noted that the AfD has been particularly strong in Germany’s “new” states almost from the beginning (Betz and Habersack 2019, 2019; Pesthy, Mader, and Schoen 2020; Arzheimer and Berning 2019; Weisskircher 2020). I will first demonstrate that the AfD’s eastern branches and the party’s disproportionate support in the “new” states were crucial for its breakthrough and subsequent ascendancy (section 2). I will then show that the AfD’s lopsided electoral success can be fully explained by significantly higher levels of nativism in the eastern population (section 3). Once these are taken into account, the party enjoys no particular advantages in the eastern states.

Easterners also display higher levels of right-wing extremism and populism than their western compatriots. It is at least plausible that this environment has shaped the development of the eastern party branches, both through recruitment effects and through attempts to appeal to this specific constituency. One should note, however, that right-wing extremism and populism have no additional positive effect on AfD voting in the east once nativism is controlled for. Moreover, extremist and populist tendencies within the AfD are by no means confined to the east, as will be shown in the next section. Before embarking on this analysis, the elements of the underlying framework1 (which draws heavily on Mudde 2007, 2019) should be introduced briefly.

Nativism is the central tenet for all far-right actors and their supporters. It is a world view that combines xenophobia and nationalism and holds that non-native elements (persons and ideas) are a threat to the ethnically and culturally homogeneous nation-state (Mudde 2007, 19).

Nativism is a necessary but insufficient condition for being classified as far right. Following Mudde (2007, 22–23) and his reading of Altemeyer (1981), right-wing authoritarianism is the second essential feature that sets far right apart from other rightist actors. Its key elements are an excessive level of support for established cultural norms and practices (conventionalism), a reverence for strong leadership (authoritarian submission), and, perhaps most crucially, hostility towards outgroups (authoritarian aggression).

Within the far right, a further distinction can be made between radicals and extremists (Mudde 2007 ch. 1), which differ in their approach to democracy. Extremists want to replace the democratic order with some autocratic system. A positive view of past authoritarian regimes and their ideologies (most notably National Socialism) is a sufficient condition for extremism.

Conversely, radicals shy away from open attacks on democracy itself and may even claim to be democracy’s true defenders. This is particularly true for actors that also espouse populism: a “thin ideology” that pits the pure people against a corrupt elite and reduces democracy to the rule of a majority that is unfettered by minority rights and liberals institutions such as courts and parliaments (Mudde 2007, 21–23).

Empirically, the lines between these categories are sometimes blurry, but they have considerable analytical value. More specifically, they are useful for describing the AfD’s trajectory, its appeal to voters, and the nature of its persistent internal conflicts.

The AfD’s breakthrough, transformation and rise, and the role of the eastern states

Over its short history, the AfD underwent a remarkable transformation (see (Arzheimer 2019; Betz and Habersack 2019; Lees 2018)). The AfD began its life in 2013 as a soft eurosceptic project that billed itself as “liberal-conservative”, i.e. economically liberal yet socially conservative. Its most prominent leaders had been (or could have been) members of the CDU and the FDP. While their early manifestos put them unambiguously on the right and while both the rank and file and the leadership were ideologically heterogeneous, the party was neither radical nor particularly populist during the 2013/14 period (Arzheimer 2015).

In the beginning, there was also nothing that would have suggested an especially “eastern” profile of the party. The party was formally founded in Oberursel, a prosperous town near the western financial centre of Frankfort, by a small group of mostly western men.2 Alexander Gauland, one of the most influential figures in the AfD who would go on to lead the party in Brandenburg and became leader of both the delegation in the Bundestag and the national party in 2017 had been born in the eastern city of Chemnitz in 1941. But Gauland fled from the GDR in 1959. He had a career as a bureaucrat and politician in the western state of Hesse and was a member of the old FRG’s elite for about three decades before he became a newspaper editor, journalist, and writer in Brandenburg and Berlin in the 1990s.

The only prominent easterner at the time was Frauke Petry, who became party leader in Saxony and was elected as one of the AfD’s three “speakers” (party leaders with equal rights) at the first party conference in 2013. But even Petry’s biography was hardly typical: while she was born in Dresden in 1975, her family moved to the Ruhr area in 1990. After finishing secondary school, Petry won a scholarship for the University of Reading in the UK, where she completed a BSc. This was followed by a postgraduate degree, a PhD, and a postdoc at the University of Göttingen. She only moved back to the eastern states in 2007 to set up a company. Similarly, two other party leaders that rose to prominence in the east – Björn Höcke and Andreas Kalbitz – both grew up in western states and only moved to the east in the 2000s when both men were already in their 30s.

1Mudde (2007) developed this framework for classifying parties and their ideologies, but it is straightforward to extend it to to non-partisan collective actors (e.g. social movement organisations) as well as to the individual attitudes of citizens, members, and activists.

While it is true that the AfD’s eastern state party chapters quickly began to appeal to regional and even sub-regional identities and issues (Weisskircher 2020, 4), this is what all parties do in Germany’s decentralised political system. It was only during the radicalisation of the AfD that some eastern politicians began to make claims on the legacy of the eastern dissidents and the peaceful revolution, mirroring a similar rhetoric deployed by Pegida. Even then, the AfD as a whole carefully steered clear of presenting itself as a regional political force, which would have alienated western voters.

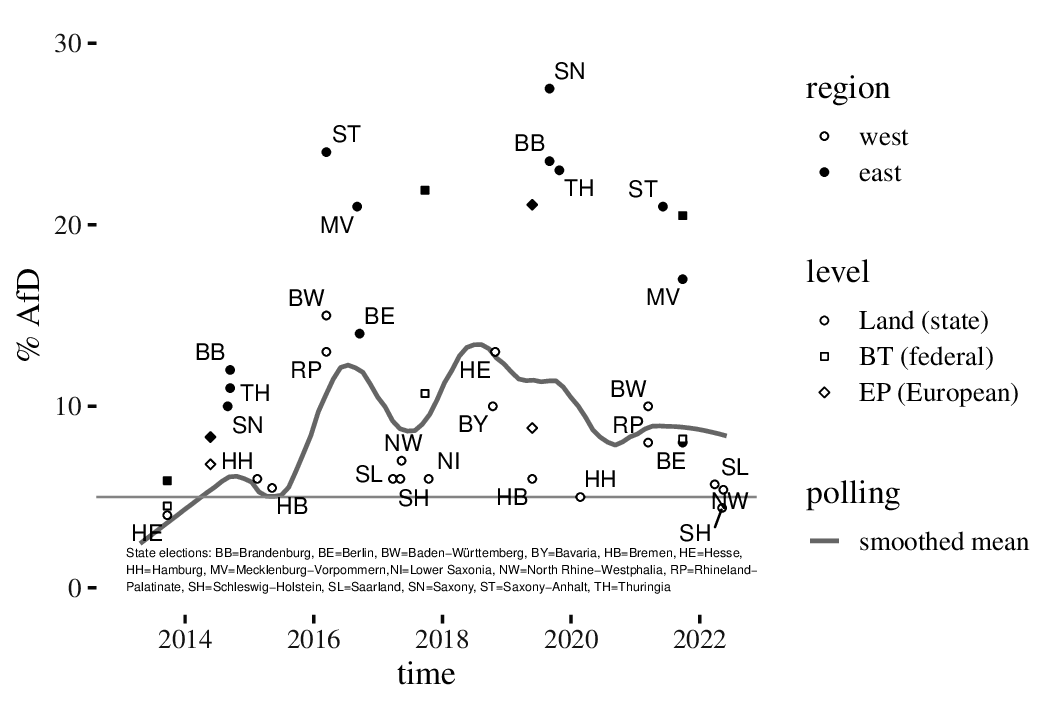

How did these issues of regional appeal and identity play out in terms of popular support? Figure 1 addresses this question. The dark gray line shows support for the AfD in national polls, which was constructed by locally smoothing over the headline numbers from the “Politbarometer” and “Deutschlandtrend” series.1 The various symbols in Figure 1 represent election results at the Land (circles), federal (squares), and European (diamond) levels. Hollow symbols stand for individual western states (Land elections), or results aggregated over all western states (federal and European elections). Filled symbols represent the analogous numbers for the eastern states.

The leftmost symbols in the plot show that even in the 2013 federal election when the party’s image was shaped by members of the western elites, the AfD was slightly more successful in the east. The difference is tiny in absolute numbers (1.5 percentage points) but may have been of psychological relevance for party activists, as it put the party just above the electoral threshold in the east.

This (relatively small) east-west difference was replicated eight months later when the AfD won its first seats ever on a vote share of 7.1 per cent in the European parliamentary election. However, the party’s public perception at this time was dominated Bernd Lucke, a professor of economics at the University of Hamburg, another westerner to whom the media often simply referred as “the founder” of the party. Lucke led the slate of candidates for the European Parliament, all of whom had a similarly western background (Arzheimer 2015, 552).

At what point in the trajectory did the AfD’s breakthrough occur? As Art (2011, 4) observes, there is no undisputed definition of “what constitutes an electoral breakthrough” in the literature. Although the AfD remained just below the threshold in the 2013 federal election, their vote share of 4.7 per cent was certainly enough to “attract the attention of the media and other political parties”, one potential criterion mentioned by Art.

Conversely, their good result in the European election was perhaps less relevant for establishing the party as a relevant player than it seemed at the time. First, turnout (48 per cent) and public interest in the election were low, and there was no (explicit) electoral threshold so that a whole host of non-established parties won seats.2 Second, German media rarely report on MEPs and their work and do not treat politicians in the European arena as on par with the national or regional ones. Third, and relatedly, Lucke and the other members of the AfD’s delegation spent at significant amount of their time in Brussels and Strasbourg, which somewhat isolated them from their fellow party members.

In short, the European election result alone would probably not have conferred “persistence” (Art 2011), but the elections in the eastern states of Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia that followed in August and September certainly did. At a time when the national polling average was barely above the electoral threshold, the eastern state parties won between ten and twelve per cent of the vote. This gave the party 36 state-level MPs, all based in (eastern) state captials and equipped with considerable resources. Each single state party delegation was bigger than the AfD group in the European Parliament.

Apart from a focus on regional instead of European issues, the manifestos in Brandenburg and Thuringia very much resembled the European one. All three stated a preference for a “Canadian style” point-based immigration regime and discussed migration almost exclusively in economic terms. While they had a socially conservative slant and while the Thuringian manifesto featured an early attack on “political correctness”, none of the three contained any statements on religion (often a proxy issue for immigration from predominantly Muslim societies, see Züquete (2008)). However, the respective party leaders and frontrunner candidates, Alexander Gauland and Björn Höcke, already departed from this script on the stump by framing immigration as a cultural threat and making this their main issue.

The Saxonian manifesto was presumably the first AfD document that explicitly mentioned Muslims by demanding referenda on plans to build mosques with minarets (section IV.2.5). The AfD also warned of a “de-legitimisation of citizen protests [against mosques]” that presaged the “Pegida” movement which began in October 2014, and campaigned against “integration folklore” including anti-discrimination courses. Three months later Petry said that Pegida represented “issues that had been neglected by politicians” while members of the state party leadership joined in the protests (FAZ 11.12.2014, page 4). The AfD’s delegation in the Saxony parliament met with Pegida’s leadership in January 2015 but could not agree on a closer co-operation, not least because of personal animosities. At the grassroots level, however, there was a substantial overlap between AfD and Pegida activists (Vorländer, Herold, and Schäller 2016, 39–43).

The twin question of the party’s relationship with Pegida and other far-right actors and its position on right-wing populism more generally soon evolved into a major cleavage within the AfD. Early in 2015, it became linked to the conflict over Lucke’s attempts to centralise power in his own hands. Nationwide support for the AfD was stagnating at best (see Figure 1), and the party barely scraped past the electoral threshold in the city states of Hamburg (Lucke’s home state) and Bremen. The (mostly western) “liberal-conservatives” blamed this on the attempts to move the party further to the right, while the (mostly eastern) proponents of this new course pointed out that the Hamburg and Bremen state parties had failed to capitalise on the immigration issue and had not invited successful eastern leaders such as Gauland and Petry to campaign (FAZ 17.02.2015, page 4).

In March 2015, some of the right-most party members launched the “Erfurt resolution”, a rallying cry against Lucke’s alleged attempts to bring the AfD into the mainstream (Arzheimer 2019, 92–93). Supporters of the resolution became known as the “wing”, an informal faction within the party whose influence grew over the years. The meetings of the wing were named for the Kyffhäuser monument in the eastern state of Thuringia, which has been a focus of right-wing extremist mobilisation since the 1890s. Three of the most prominent members of the wing – Björn Höcke, Andreas Kalbitz, and Andre Poggenburg – were or would become leaders of eastern state parties, and Gauland signed the resolution during his tenure as party leader in Brandenburg. A related network, the “patriotic platform”, which partly overlapped with the wing and was disbanded in 2018, was also largely based in the east, although neither was exclusively eastern.

After the Bremen election in May, Lucke emailed all party members and urged them to support a competing manifesto/faction called “Weckruf” (wake-up call). At the request of his co-leaders, Lucke was subsequently locked out of the internal mailing system (FAZ.NET 18.05.2015). After Petry reached an agreement with the ultra-rights within the party at the party conference in July 2015, Lucke, four of the other six MEPs, and about ten per cent of the members including a number of mid-level functionaries left the AfD.

This conflict had two major consequences. First, the party’s leadership structure remains highly fragmented even by German standards. Public disagreement between the two remaining speakers and within the national executive is frequent, and the state-level chapters retain a high degree of autonomy. Second, Frauke Petry, who replaced Lucke as the AfD’s most prominent face, first encouraged, then failed to contain a shift to the right. Under her stewardship, the AfD became a more or less normal radical right party, and their electorate changed accordingly (Arzheimer and Berning 2019).

As depicted in Figure 1, support for the AfD hovered below or just above the electoral threshold during and after the power struggle. Apart from the two remaining MEPs, Marcus Pretzel (who also led the state party in North Rhine-Westphalia) and Beatrix von Storch (who became leader of the Berlin state party in 2016), the eastern state MPs were the only party members holding public offices, and the AfD looked very much like another failed far-right project.

Support for the transformed party began to rise again towards the end of 2015 against the backdrop of the so-called refugee crisis (according to Gauland “a present for the party” (Der Spiegel, 12.12.2015) and reached between 12 and 15 per cent in nationwide polls. In the 2016 Baden-Württemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate state elections, the party won bigger vote shares than any far-right party had since the war. But these results paled in comparison to the eastern state of Saxony-Anhalt, where a particularly right-leaning state party led by Poggenburg won almost a quarter of the vote.

Conversely, their results in a string of western state elections held in the spring of 2017 were disappointing for the party, reflecting both a decline in national polls and persistent east-west differences. Just before the federal election in September 2017, the AfD had won 73 seats in western state parliaments but 100 seats in the east.

In the 2017 Bundestag election, the AfD did comparatively well in the west (11 per cent) but extraordinarily well in the east (22 per cent). Although less than a quarter of the population lives in the eastern states including Berlin and although turnout is lower in the east (which affects territorial representation), about one third of the 94 new federal MPs were elected in the east. Put differently, while about 25 per cent of the party members lived in the eastern states (Niedermayer 2019, 6, 19), they made up roughly one half of the party elite. The extraordinary good results in the 2019 eastern state elections have further tilted this balance.

Since the 2017 election, national support for the AfD has waxed and then waned as immigration moved down the political agenda and the most extreme elements within the party came under scrutiny by the media and the authorities, but the general pattern in Figure 1 has remained stable: with the exception of Berlin (an atypical eastern state), support for the AfD is twice, if not three times higher in the east than in the west for both state and national elections.

Marked differences in support for radical right parties are not unusual per se. The French Rassemblement National (formerly the Front National) has longstanding strongholds in the south, the north east, and now also in the north west, that partly represent urban/rural and economic cleavages. The Italian Lega began its life as a regionalist and even nominally separatist party, and the Vlaams Belang is confined to Flanders and Brussels.

What sets the AfD apart from other radical right parties in Europe is first that they are cultivating ties to right-wing extremist actors, with openly extremist ideas and codes becoming more acceptable within the party, particularly since the 2017 election. These developments are often attributed to the growing influence of the wing faction. At the time of writing, the wing had come under surveillance by the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and had disbanded at the request of the national executive in April 2020. As the wing never had any formal structures and as its members were not expelled from the party proper, this was widely seen as a diversion. In May 2020, a slim majority of the national executive also voted to declare Kalbitz’s membership null and void, because he had failed to declare previous memberships in extremist organisations, but Kalbitz is currently fighting this decision in the courts.

Second, extremist tendencies seem to be particularly pronounced in the east on both the elite and the voter level.3 This raises profound and uncomfortable questions about the state of democracy and political culture after unification, which I will address in the next section.

A micro-level model of the AfD vote in east-west perspective

In the previous section I have shown that the AfD is disproportionately successful in the “new” states, where it often presents a more openly extremist facade than in the west. At the same time, eastern levels of nativist attitudes and right-wing extremist activism and violence have been substantially higher than in the west ever since unification (see e.g. (Kurthen, Bergmann, and Erb 1997), (Rucht 2018), and the chapter by Jäckle and König in this volume). Taken together, this suggests that east-west differences in support for the AfD result from underlying differences in demand for populist and far-right politics.

To test this assertion, this chapter will explore three closely related questions:

- Are populist, nativist, and extremist attitudes really more prevalent in the eastern states?

- Do these attitudes have a stronger or otherwise diverging impact on voting behaviour in the east?

- Are attitudinal differences in level and effect sufficient to explain the diverging appeal of the AfD, or is there an additional, region-specific component to the AfD’s success in the east?

Addressing these questions requires both adequate data and a statistical model for estimating the prevalence and electoral impact of these attitudes. Because constructs such as nativism are complex and not directly observable, each of the attitudinal variables should be operationalised by multiple indicators.

A recent wave of Germany’s General Social Survey (ALLBUS) provides data that are almost ideally suited to address these questions. Field work took place from April 2018 until September 2018, a period when the AfD had become a nationwide political force whose connections to right-wing extremists actors were discussed more widely than before.

The ALLBUS includes a host of items designed to measure specific backlash against immigration and immigrants as well as more general nativist tendencies. While it lacks items that measure authoritarianism, the survey also encompasses a scale specifically designed to measure populist attitudes.

The ALLBUS also replicates a right-wing extremism scale that was developed at the height of the third wave of right-wing mobilisation during the 1990s. Many items in this battery refer to elements of traditional German right-wing extremism that are rarely polled, including positive evaluations of Hitler and the Nazi regime and support for violence against out-group members.4 Tables 1, 2, and 3 give an overview of how the constructs were operationalised.

[tab-populism-indicators]Indicators for populism| Variable | Text |

|---|---|

| (pop01/pa29) | (The Members of the Bundestag must only be bound to the will of the people.) |

| pop02/pa30 | Politicians talk too much and do too little. |

| pop03/pa31 | An ordinary citizen would represent my interests better than a professional politician. |

| pop04/pa32 | What they call compromise in politics is in reality just a betrayal of principles. |

| pop05/pa33 | The people and not politicians should make the important political decisions. |

| pop06/pa34 | The people basically agree what needs to happen politically. |

| pop07/pa35 | Politicians only care about the interests of the rich and powerful. |

| Note: The first variable name (e.g. pop01) is the one used in the replication files, the second one (e.g. pa29) is the name in the original ALLBUS data set (ZA 5270). Where necessary, variables were recoded so that higher numerical values correspond to stronger populist orientations. |

| Variable | Text |

|---|---|

| (px03) | (In some circumstances a dictatorship is a better form of government. ) |

| px04 | National Socialism also had its good sides. |

| px05 | If it hadn’t been for the holocaust Hitler would be regarded as a great statesman today. |

| px08 | The Jews still have too much influence. |

| px09 | There is something peculiarly different about the Jews which stops them from fitting in with us. |

| px10 | I can understand that people carry out attacks on homes for asylum seekers. |

| Note: Variable names are the same for both the replication files and the original ALLBUS data set (ZA 5270). Variables are coded so that higher numerical values correspond to stronger right-wing extremist orientations. | |

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| (px01) | (I am proud to be German) |

| px02 | It’s about time we found the courage to have strong national feelings again |

| px06 | Because of its many resident foreigners, Germany is dominated by foreign influences to a dangerous degree |

| px07 | Foreigners should always marry people from their own ethnic group |

| mig1/pa09 | Immigrants should be required to adapt to German customs and traditions |

| mig2/pa17 | Immigrants are good for Germany’s economy (rev) |

| mig3/pa19 | The influx of refugees to Germany should be stopped |

| mig4/mp16 | Refugees: a risk for the welfare state |

| mig5/mp17 | Refugees: a security risk |

| mig6/mp18 | Refugees: a risk for social cohesion |

| mig7/mp19 | Refugees a risk for the economy |

| Note: The first variable name (e.g. mig1) is the one used in the replication files, the second one (e.g. pa09) is the name in the original ALLBUS data set (ZA 5270). Variable names starting with px were retained. Where necessary, variables were recoded so that higher numerical values correspond to stronger nativist orientations. |

Structural equation modelling (SEM) provides the natural framework for analysing these data. SEM simultaneously estimates measurement models for the attitudinal variables as well as a structural model that links them to (intended) voting behaviour, with estimates that are corrected for measurement error.

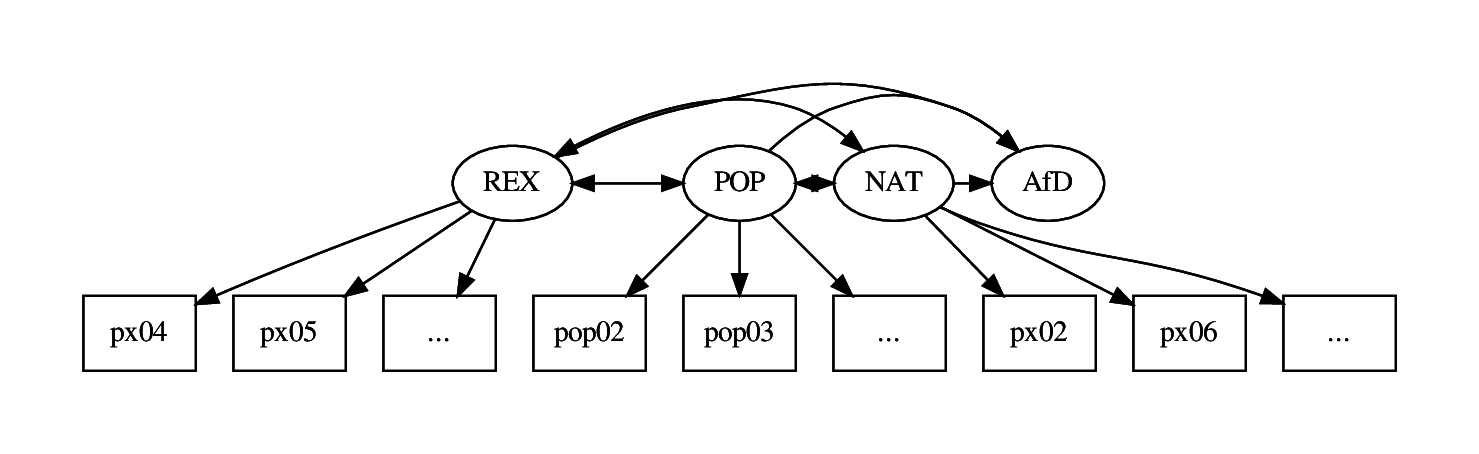

Figure 2 shows the overall structure of the model. Right-wing extremism, populism, and nativism are latent variables that may be positively related to each other. They are all assumed to have positive effects on voting for the AfD. The size of these effects and the strength of their inter-relationships are allowed to vary across regions. The means of the attitudinal constructs are allowed to vary, too.

However, for interregional comparisons to be valid, the measurement models need to work in equivalent ways in both parts of Germany. More formally, at least “scalar invariance” of the measurement models is required. Scalar invariance means that for all indicators, both the intercepts and the factor loadings can be constrained to be the same across regions (Davidov 2009, 69) while still achieving a good model fit.1 Measurement errors may vary under scalar invariance.

A preliminary measurement-only model shows that three items are unreliable and should be removed from their scales.2 One of them (px03) was also responsible for the only substantive regional difference in measurement errors. Without the offending item, the model can be re-specified under the assumption of “strict invariance”, i.e. with identical measurement errors across both regions, which makes it much more parsimonious.

All latent variables were given variances of one. Their covariances therefore reduce to correlations, and factor loadings reflect a change of one standard deviation in the latent variable. Because voting intention was modelled as a binary3 choice (AfD vs any other party), the effects on this variable (Table 7) are probit coefficients. All other relationships are linear.

Estimation was carried out in MPlus 8.2, using the WLSMV estimator, which handles missing values in a transparent fashion. Even under strict invariance, the model fit is excellent with an RMSEA of 0.033 (CI 0.031; 0.035).

Table 4 shows the intercepts and factor loadings for all 21 indicators as well their residual variances. In sum, the results demonstrate that the remaining 21 items are reliable indicators for the latent variables.

[mtable]Measurement models| loadings | intercepts | residual variances | |

|---|---|---|---|

| POP2 | 0.66*** | 3.92*** | 0.52*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| POP3 | 0.75*** | 2.69*** | 0.87*** |

| (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| POP4 | 0.83*** | 3.00*** | 0.61*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| POP5 | 0.69*** | 2.99*** | 0.95*** |

| (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| POP6 | 0.65*** | 2.79*** | 0.96*** |

| (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| POP7 | 0.68*** | 3.10*** | 0.73*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| PX02 | 0.56*** | 3.70*** | 0.96*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | |

| MIG1 | 0.60*** | 4.06*** | 0.67*** |

| (0.02) | (0.03) | (0.02) | |

| MIG2 | -0.66*** | 3.36*** | 0.77*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| MIG3 | 1.01*** | 2.71*** | 0.68*** |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.02) | |

| MIG4 | 0.64*** | 3.70*** | 0.51*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | |

| MIG5 | 0.54*** | 3.94*** | 0.34*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.01) | |

| MIG6 | 0.68*** | 3.34*** | 0.62*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| MIG7 | 0.74*** | 3.00*** | 0.60*** |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| PX06 | 1.15*** | 2.77*** | 0.64*** |

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.02) | |

| PX07 | 0.59*** | 1.84*** | 0.88*** |

| (0.02) | (0.03) | (0.03) | |

| PX04 | 0.70*** | 1.63*** | 0.64*** |

| (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.02) | |

| PX05 | 0.53*** | 1.57*** | 0.85*** |

| (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |

| PX08 | 0.82*** | 1.79*** | 0.65*** |

| (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |

| PX09 | 0.68*** | 1.64*** | 0.58*** |

| (0.02) | (0.04) | (0.02) | |

| PX10 | 0.50*** | 1.36*** | 0.60*** |

| (0.02) | (0.04) | (0.02) |

| West | East | |

|---|---|---|

| Right-wing extremism with Nativism | 0.63*** | 0.62*** |

| (0.02) | (0.04) | |

| Right-wing extremism with Populism | 0.45*** | 0.52*** |

| (0.03) | (0.05) | |

| Nativism with Populism | 0.60*** | 0.67*** |

| (0.02) | (0.04) |

Before turning to the attitudes and their impact on the AfD vote, it is worthwhile to consider the relationships between nativism, populism, and right-wing extremism. Although these attitudes are conceptually different, Table 5 shows that they are highly intercorrelated, with correlations ranging from 0.45 to 0.67 and being virtually identical across both regions. Substantively, these correlations imply that they share up to 45 per cent of their variances. In other words, someone who scores particularly high/low on one concept is also likely to score high/low on the other two. Importantly, the relationship is strong but by no means perfect, which means that the effects of all three variables remain separable and can be estimated net of each other.

As the measurement models for the three scales are invariant across regions, the first of this section’s guiding questions can be answered readily: Table 6 demonstrates that easterners and westerners differ significantly on all three dimensions. Differences are particularly large for populism and nativism with values just below/above 0.4.

[means]Attitudinal east-west differences| East-West differences | |

|---|---|

| Populism | 0.38*** |

| (0.04) | |

| Nativism | 0.41*** |

| (0.04) | |

| Right-wing extremism | 0.16* |

| (0.07) |

Because the latent variables were given unit variance, these differences are standard deviations. As the latent variables are normally distributed, about 50 per cent of respondents will have scale values no more than 0.674 standard deviations above or below the mean, with 90 per cent of respondents falling between 1.64 standard deviations from the mean.

However, the substantive meaning of the parameters in Table 6 is hard to grasp. What exactly does an average difference of 0.4 standard deviations imply? A thought experiment may be helpful: if one would randomly select pairs of respondents from both regions, six out of ten times the easterner would hold more extreme views than the westerner. In five of ten cases, this difference would amount to more than half a point on the scale, and in roughly four out of ten cases, the gap would be wider than one scale point.

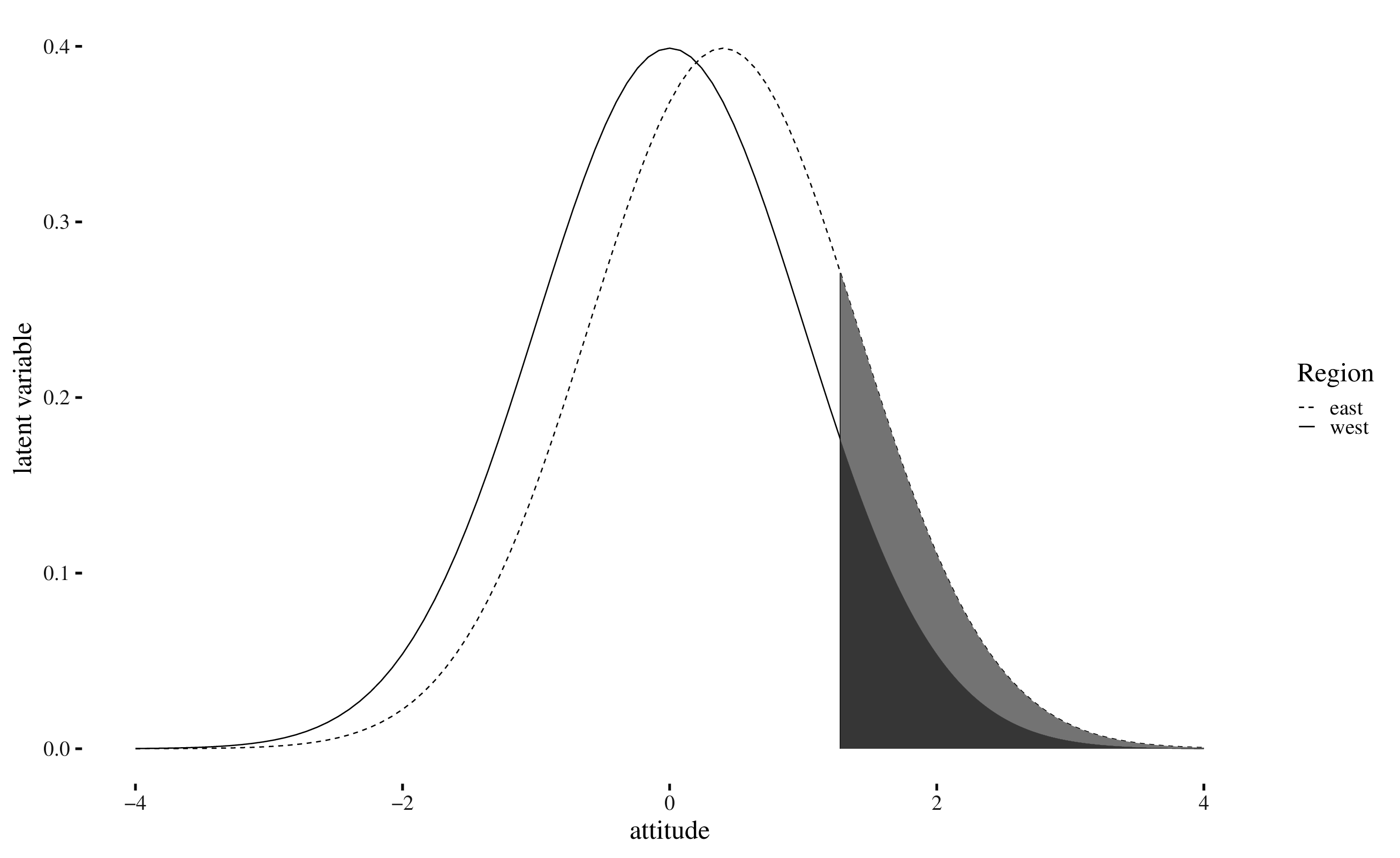

Figure 3 further helps to illustrate the implications. While there is considerable overlap between both distributions, their pointed shape means that there are substantial gaps at the margins. For example, only ten percent of western respondents have a score of more than 1.28 on the nativism scale (the darker shaded area under the solid curve). In the east, this share is about twice as high (the total shaded area under the dotted curve).

[coefficients]Regression of AfD vote on extremism, nativism, and populism| West | East | |

|---|---|---|

| Right-wing extremism | -0.15* | -0.04 |

| (0.06) | (0.08) | |

| Nativism | 0.78*** | 0.81*** |

| (0.07) | (0.11) | |

| Populism | 0.20*** | 0.04 |

| (0.05) | (0.09) | |

| Constant | -1.46*** | -1.40*** |

| (0.04) | (0.05) |

To ascertain whether these attitudinal differences are big enough to fully account for the differences in the AfD’s success across regions, one needs to address the second guiding question, i.e. consider the size of the effects that the attitudes have on the AfD vote. Table 7 shows the probit regression of voting for the AfD on nativism, populism, and right-wing extremism. In the west, nativism has a strong positive effect. Populism has a considerably weaker (but still significant) positive effect, too. Right-wing extremism has an effect that is comparable in magnitude to populism but negative. There is no obvious explanation for this unexpected negative sign.1

In the east, estimates are less precise because the size of the subsample is smaller. Controlling for nativism, neither the effect of right-wing extremism nor the effect of populism is significantly different from zero. However, like in the west, nativism exerts a very strong effect. In sum, while populism and extremism have slightly different (non-)effects, these differences cannot be responsible for the higher levels of AfD support in the eastern states.

Conversely, the effect of nativism and also the constant are virtually identical across regions. The constant gives the “probit” (a non-linear transformation of probabilities) of AfD voting for respondents whose levels of nativism, populism, and extremism are exactly zero, i.e. at the western averages. Reversing the probit transformation by plugging the constant into the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal yields the predicted probability of an AfD vote for such a person: 8 per cent. Importantly, this value does not differ significantly across regions. This finding is the answer to the third question: if easterners were on average just as nativist, populist and right-wing extremist as their western compatriots, the party would have no specific advantage in the eastern states. Higher levels of nativism are the driving force behind the AfD’s disproportionate success in the eastern states.

1Voters for “other” parties including the NPD and even smaller splinter groups had been excluded from the analysis, ruling out the notion that the AfD could be perceived as too tame for true extremists. One should, however, bear in mind the ceteris paribus nature of the statistical model and the strong correlations amongst the three attitudinal variables: someone who scores high on the right-wing extremism scale probably also scores high on the other two, and the dominant positive effect will still push them towards the AfD.

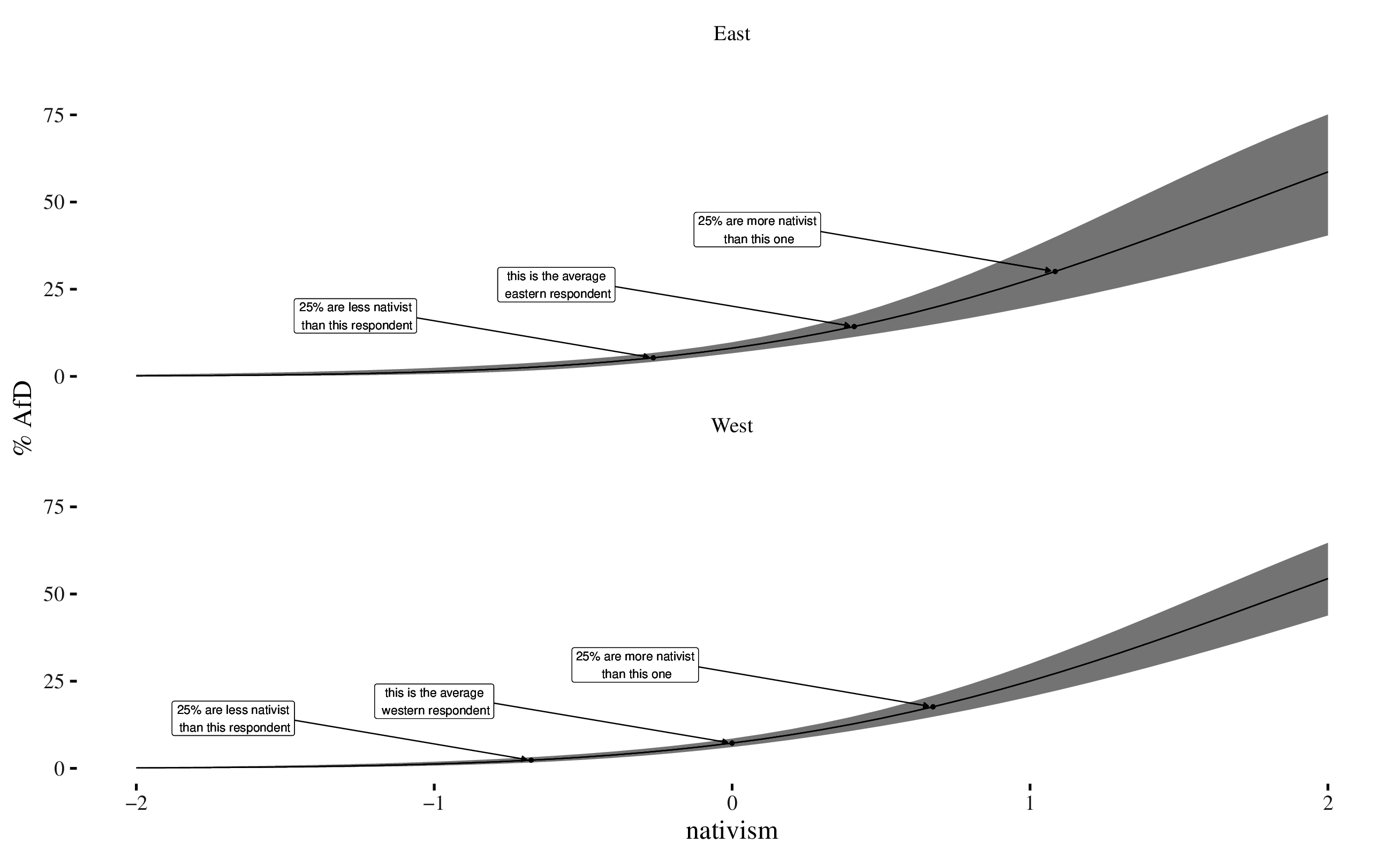

To illustrate what this means in terms of political support for the AfD, Figure 4 shows how AfD voting depends on nativism, and how the difference in the distribution of nativist attitudes affects the party’s fortunes in both regions. In the west, 25 per cent of the respondents have nativism scores of -0.67 or less, which translates to a probability of AfD voting of no more than 2.5 per cent. Another 25 per cent register values of 0.67 and more on the nativism scale, which result in a predicted probability of at least 17.5 per cent. For the average west German respondent, the predicted probability of an AfD vote is about 7 per cent.

In the east, 25 per cent of the respondents have nativism scores of less than -0.26, which comes close to the west German average and translates to just over 5 per cent AfD support. The upper 25 per cent of respondents have nativism scores in excess of 1.08, and their propensity to vote for the AfD is at least 30 per cent. Finally, the mean nativism score for the eastern states is 0.41 (i.e. closer to the upper western quartile than to the western mean), resulting in a predicted probability of just over 14 per cent.

In sum, the model predicts that the prevalence of nativism in eastern Germany should lead to levels of AfD support that are roughly twice as high as in the west. This is broadly in line with the actual electoral results presented in the previous section.

Discussion and Conclusion

The AfD is Germany’s first nationally successful radical right party. It is not a regional party, but a longitudinal analysis of electoral results and polling data shows that its disproportionate success in the eastern state was critical for its breakthrough and survival during its early years. Even today, the party would come uncomfortably close to the electoral threshold without its voter base in the eastern states.

Unlike many other radical right parties, the AfD has moved closer towards traditional right-wing extremism over time, and existing ties to far-right actors have become more visible. Predominantly eastern networks within the party have played an important but by no means exclusive role in these developments. Commercial surveys such as the “Politbarometer” series suggest that this limits the party’s electoral prospects, as a large segment of the population sees the party as unelectable. And yet, the AfD is the second-strongest party in large swaths of the eastern states (Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia in particular), suggesting a much bigger appetite for radical or even extremist right-wing politics in the former GDR.

Using psychometric scaling techniques and high-quality survey data from the ALLBUS series, it could be shown that respondents from the eastern states are indeed on average substantially more nativist and more populist than their western compatriots. Easterners are also more right-wing extremist, but this difference is smaller. One should, however, note that nativism, populism, and right-wing extremism are positively intercorrelated in both regions.

These findings align well with previous research on east-west differences, but contrast slightly with Pesthy, Mader, and Schoen (2020), who find relatively small east-west differences for populism and nativism. One possible explanation is that Pesthy, Mader, and Schoen (2020) use fewer and slightly different indicators, rely chiefly on simpler additive indices, and use online panel data that could be more strongly effected by self-selection effects than the ALLBUS sample, which was interviewed face-to-face.

The strong attitudinal east-west differences suggest that the potential for far-right parties is substantially higher in the east than in the west. Moreover, the ALLBUS data also show that nativism has a strong and consistent effect on the AfD vote. Given the size of this effect, the difference in average levels of nativism is sufficient to account for the AfD’s disproportionate levels of support in the east. Right-wing extremism and populism have much weaker effects on the AfD vote, which are also not consistent across regions. Again, this chimes with Pesthy, Mader, and Schoen’s results.

Taken together, these findings support journalistic narratives and scientific explanations which link the “collective psychological shocks, traumas and injuries sustained in the years following unification” (Betz and Habersack 2019, 116) to higher levels of nativism. Related and compatible explanations point to the GDR’s “legacy of a failed anti-fascist strategy” (Backer 2000, 104), the lack of opportunities for (positive) inter-ethnic contact (Wagner et al. 2003), and self-selection effects that led to an exodus of younger and better educated citizens (particularly females) from the east (Melzer 2013), who are less likely to support the far right.

Within the confines of this chapter and with the data at hand, it is impossible to empirically separate their relative importance of these mechanisms. However, all these explanations point to factors that are stable in the medium- to long-term. This suggests that eastern demand for far-right politics, and by implication for a radical and even extremist AfD, is here to stay.

References

Altemeyer, Bob. 1981. Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Winnipeg: The University of Manitoba Press.

Art, David. 2011. Inside the Radical Right. The Development of Anti-Immigrant Parties in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Arzheimer, Kai. 2015. “The Afd: Finally a Successful Right-Wing Populist Eurosceptic Party for Germany?” West European Politics 38: 535–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1004230.

———. 2019. “Don”t Mention the War! How Populist Right-Wing Radicalism Became (Almost) Normal in Germany.” Journal of Common Market Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12920.

Arzheimer, Kai, and Carl Berning. 2019. “How the Alternative for Germany (Afd) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right, 2013-2017.” Electoral Studies, online first. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004.

Backer, Susann. 2000. “Right-Wing Extremism in Unified Germany.” In The Politics of the Extreme Right. From the Margins to the Mainstream, edited by Paul Hainsworth, 87–120. London, New York: Pinter.

Betz, Hans-Georg, and Fabian Habersack. 2019. “Regional Nativism in East Germany. The Case of the Afd.” In The People and the Nation. Populism and Ethno-Territorial Politics in Europe, edited by Reinhard Heinisch, Emanuele Massetti, and Oscar Mazzoleni, 110–35. London: Routledge.

Davidov, Eldad. 2009. “Measurement Equivalence of Nationalism and Constructive Patriotism in the Issp: 34 Countries in a Comparative Perspective.” Political Analysis 17 (1): 64–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpn014.

Kurthen, Hermann, Werner Bergmann, and Rainer Erb, eds. 1997. Antisemitism and Xenophobia in Germany After Unification. Oxford University Press.

Lees, Charles. 2018. “The ‘Alternative for Germany’: The Rise of Right-Wing Populism at the Heart of Europe.” Politics, online first. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263395718777718.

Melzer, Silvia Maja. 2013. “Reconsidering the Effect of Education on East-West Migration in Germany.” European Sociological Review 29 (2): 210–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcr056.

Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2019. The Far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Niedermayer, Oskar. 2019. Parteimitglieder in Deutschland, Version 2019. Arbeitshefte Aus Dem Otto-Stammer-Zentrum 30. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin. https://www.polsoz.fu-berlin.de/polwiss/forschung/systeme/empsoz/team/ehemalige/Publikationen/schriften/Arbeitshefte/Arbeitsheft-Nr-30_2019.pdf.

Pesthy, Maria, Matthias Mader, and Harald Schoen. 2020. “Why Is the Afd so Successful in Eastern Germany? An Analysis of the Ideational Foundations of the Afd Vote in the 2017 Federal Election.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift online first.

Rucht, Dieter. 2018. “Mobilization Against Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Germany: A Social Movement Perspective.” In Protest Movements in Asylum and Deportation, edited by Sieglinde Rosenberger, Verena Stern, and Nina Merhaut, 225–45. Cham: Springer Open. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-74696-8_11.

Vorländer, Hans, Maik Herold, and Steven Schäller. 2016. Pegida. Entwicklung, Zusammensetzung Und Deutung Einer Empörungsbewegung. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Wagner, Ulrich, Rolf van Dick, Thomas F. Pettigrew, and Oliver Christ. 2003. “Ethnic Prejudice in East and West Germany: The Explanatory Power of Intergroup Contact.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 6 (1): 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430203006001010.

Weisskircher, Manès. 2020. “The Strength of Far-Right Afd in Eastern Germany: The East-West Divide and the Multiple Causes Behind ‘Populism’.” The Political Quarterly, online first. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12859.

Züquete, Josë Pedro. 2008. “The European Extreme-Right and Islam. New Directions?” Journal of Political Ideologies 13 (3): 321–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569310802377019.

1For each indicator, its intercept represents the expected answer when the latent variable (e.g. populism) that is measured by it has a value of zero. The factor loading represents the expected change in answering behaviour when the latent variable goes up by one unit.

2px01 (national pride) and pop01 (MPs bound by will of the people) have estimated measurement errors in excess of 80 per cent across the sample. Presumably the wording of both items is too soft so that a plurality or even a majority of respondents fully agrees with the statements. The measurement error of px03 (dictatorship sometimes better) exceeds 80 per cent in the east only and was therefore dropped, too.

3The (very few) respondents who said they would not vote in a general election as well as voters for “other” parties not currently represented in the Bundestag were excluded.

1These polls are conducted by FGW and Infratest dimap and funded by Germany’s major public broadcasters ZDF and ARD, respectively. The smoothing is by local polynomial regression fitting with a span of 0.25. Because the population of the western states is roughly four times as big as the population of the eastern states, this curve is more strongly affected by public opinion in the west.

2Germany had enacted a three-per-cent threshold for European elections in 2013, but this was declared void by the Federal Constitutional Court in February 2014.

3This is partly an oversimplification, as there are plenty of examples of extremism in the western chapters, too. Katrin Ebner-Steiner, the chair of the AfD’s delegation in the Bavarian state parliament, is a member of the wing (https://www.sueddeutsche.de/bayern/afd-kathrin-ebner-steiner-greding-nationalhymne-1.4432704 (May 15, 2020)). Doris von Sayn-Wittgenstein was the AfD’s leader in Schleswig-Holstein from 2017 until 2019, when she was expelled over her relationships with a number of extremist organisations. Wolfgang Gedeon became a member for the AfD in the Baden-Württemberg state parliament in 2016. When the parliamentary leadership tried to remove the whip from him because it emerged that he had written a number of anti-semitic books, the delegation split for a while. He was only expelled from the party in 2020. In the Saarland, leader Josef Dörr and his deputy also had ties to extremists and were accused of running the small state party like a personal fiefdom. The national executive tried to disband the state party in 2016 but lost a court case. In March 2020, the national executive deposed Dörr and appointed a caretaker leadership over fresh allegations of irregularities: https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/afd-spitze-setzt-saarlaendischen-landesvorstand-ab-a-894a7c1f-571d-4d5f-a110-67a1ce23f0e4 (May 15, 2020).

4The anti-semitism items included in the original right-wing extremism scale are a borderline case. On the one hand, hostility towards Jews and other ethnic minorities that are not immigrants is an important aspect of nativism, particularly in a eastern European context where immigration is a very recent phenomenon. On the other, anti-semitism is such a crucial aspect of Nazism that I retained them as a part of the right-wing extremism scale.

2https://www.zeit.de/zeit-magazin/2017/30/alternative-fuer-deutschland-gruendung-bernd-lucke (May 20, 2020) .

Discover more from kai arzheimer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.