What?

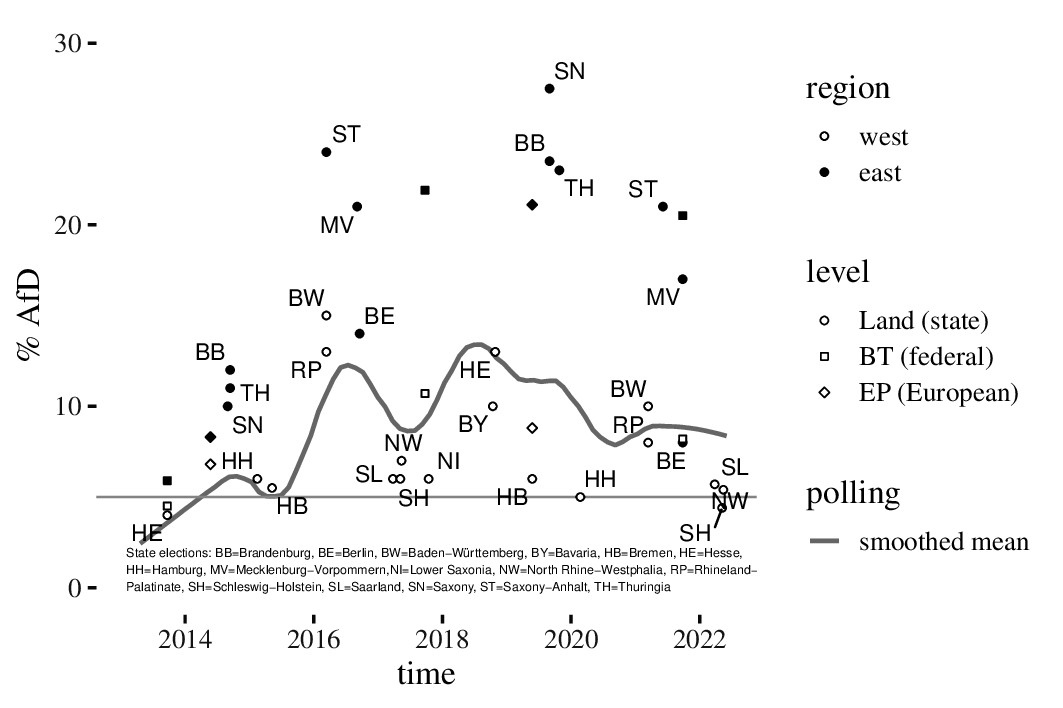

I’m currently working on a paper that looks into the role that Germany’s eastern states (aka “the new Länder”, the ex-GDR …) played for the breakthrough and the consolidation of the “Alternative for Germany” party. This figure shows support for the AfD from 2013 to 2020.

- Arzheimer, Kai. “The Electoral Breakthrough of the AfD and the East-West Divide In German Politics.” Contemporary Germany and the Fourth Wave of Far-Right Politics: From the Streets to Parliament. Ed. Weisskircher, Manès. London: Routledge, 2023. 140-158.

[BibTeX] [Abstract] [HTML]The radical right became a relevant party family in most west European polities in the 1990s and early 2000s, but Germany was a negative outlier up until very recently. Right-wing mobilisation success remained confinded to the local and regional level, as previous far-right parties never managed to escape from the shadow of “Grandpa’s Fascism”. This only changed with the rise, electoral breakthrough, and transformation of “Alternative for Germany” (AfD), which quickly became the dominant far-right actor. Germany’s “new” eastern states were crucial for the AfD’s ascendancy. In the east, the AfD began to experiment with nativist messages as early as 2014. Their electoral breakthroughs in the state elections of this year helped sustain the party through the wilderness year of 2015 and provided personel, ressources, and a template for the AfD’s transformation. Since its inception, support for the AfD in the east has been at least twice as high as in the west. This can be fully explained by substantively higher levels of nativist attitudes in the eastern population. As all alleged causes of this nativism are structural, the eastern states seem set to remain a stronghold for the far right in the medium- to long-term.

@InCollection{arzheimer-2021, author = {Arzheimer, Kai}, title = {The Electoral Breakthrough of the AfD and the East-West Divide In German Politics}, booktitle = {Contemporary Germany and the Fourth Wave of Far-Right Politics: From the Streets to Parliament}, publisher = {Routledge}, editor = {Weisskircher, Manès}, year = 2023, pages = {140-158}, address = {London}, abstract = {The radical right became a relevant party family in most west European polities in the 1990s and early 2000s, but Germany was a negative outlier up until very recently. Right-wing mobilisation success remained confinded to the local and regional level, as previous far-right parties never managed to escape from the shadow of “Grandpa’s Fascism”. This only changed with the rise, electoral breakthrough, and transformation of “Alternative for Germany” (AfD), which quickly became the dominant far-right actor. Germany’s “new” eastern states were crucial for the AfD’s ascendancy. In the east, the AfD began to experiment with nativist messages as early as 2014. Their electoral breakthroughs in the state elections of this year helped sustain the party through the wilderness year of 2015 and provided personel, ressources, and a template for the AfD’s transformation. Since its inception, support for the AfD in the east has been at least twice as high as in the west. This can be fully explained by substantively higher levels of nativist attitudes in the eastern population. As all alleged causes of this nativism are structural, the eastern states seem set to remain a stronghold for the far right in the medium- to long-term.}, keywords = {eurorex,afd}, html = {https://www.kai-arzheimer.com/paper/afd-east-west-cleavage-breakthrough/}, dateadded = {12-04-2021} }

The graph is a teeny-weeny bit busy, so here is the extended legend ? Circles are results from state (Länder elections), labelled with state codes. Squares are Bundestag, diamonds are European parliamentary elections. Filled symbols represent eastern Länder, or partial results for the eastern states only (Bundestag and EP elections). Hollow symbols represent the western states/partial western results. The blue line is the (locally smoothed) average over about 200 national elections polls from the Politbarometer (FGW) and Deutschlandtrend (Infratest-dimap) series. There are four main observations.

The eastern vote share is consistently at least two times as high as the western vote share

Not exactly a new finding, but the AfD does much better in the east than in the west. In fact, so much better that some observers see the party as specifically eastern problem. This is not correct, but the difference is striking. Even in the 2013 Bundestag election (when the AfD campaigned as a soft-eurosceptic, “liberal-conservative” outfit), the party was clearly more popular in the east. Possible reasons: fewer partisans, lower levels of institutional trust, more xenophobia.

The AfD might not have survived 2015 without the eastern states

Almost exactly 5 years ago, the AfD was almost falling apart (also see just about every other of my blog posts from that period). Support for the party fell below 5 per cent (also see the section after the next), prominent members threatened to leave or simply went. The FAZ called them, in their professional journalistic assessment, “a laughing stock”. Radically transformed (see what I did here?), the party bounced back in 2016, but during this period, their only full-time politicians with access to funding and the media (apart from two remaining MEPs) were about 30 state-level MPs who had won seats in the 2014 series of elections in Brandenburg, Saxony, and Thuringia – incidentally on platforms that presaged the AfD’s trajectory towards the Radical Right.

What role did Germany's eastern states play for the breakthrough & consolidation of the #AfD? 4 observations: vote share consistently 2-3 times higher; party might not have survived 2015 w/o east, until 2017, eastern (state) MPs outnumbered western by large margin. pic.twitter.com/8Iv7BfoZf9

— Kai Arzheimer 🇪🇺 (@kai_arzheimer) May 28, 2020

Eastern state MPs outnumbered their western counterparts until 2017

It’s not directly visible in the graph, but: the higher vote share in the east (combined with the electoral calendar, the relatively large number of eastern states, and the disproportionate size of small-state legislatures) meant that until the Bundestag election in September 2017, there were twice as many AfD (state) MPs in the east. Although the east has just over one fifth of the population and about the quarter of the AfD members, a large chunk of the party elite was recruited (though not necessarily born) in the east. Even after the 2017 election, about half of the MPs (state and federal) were eastern.

The AfD’s downward trend began long before Corona

Journalists love a good story, and they like to link the AfD’s current underwhelming performance in the polls to the fact that people are weary of populists in a crisis, and the AfD’s mixed messages on COVID. But it is also clear that the AfD’s support in national polls peaked in 2018. The declining salience of immigration and the revelations on right-wing extremists within and around the AfD have not exactly helped. Support for the party has ebbed and flowed before, and local polynomial regression by design tends to exaggerate trends at the margins of a plot, but it is clear that support began to fall months before Corona became the dominant issue in Germany and elsewhere.

Merkel kommt auch aus der DDR, oder?